Authored by Charles Hugh-Smith via oftwominds,

The global economy is toast. All that’s left is the distribution of the burned bits.

The six one-offs that drove growth and pulled the global economy out of bubble-bust recessions for the past 30 years have all reversed or dissipated. Absent these one-off drivers, the global economy is stumbling off the cliff into a deep recession without any replacement drivers. Colloquially speaking, the global economy is toast.

Here are the six one-offs that won’t be coming back:

1) China’s industrialization.

2) Growth-positive demographics.

3) Low interest rates.

4) Low debt levels.

5) Low inflation.

6) Tech productivity boom.

Cutting to the chase, China bailed the world out of the last three recessions triggered by credit-asset bubbles popping: the Asian Contagion of 1997-98, the dot-com bubble and pop of 2000-02, and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09. In each case, China’s high growth and massive issuance of stimulus and credit (a.k.a. China’s Credit Impulse) acted as catalysts to restart global expansion.

The boost phase of picking low-hanging fruit via rapid industrialization boosting mercantilist exports and building tens of millions of housing units is over. Even in 2000 when I first visited China, there were signs of overproduction / demand saturation: TV production in China in 2000 had overwhelmed global and domestic demand: everyone in China already had a TV, so what to do with the millions of TVs still being churned out?

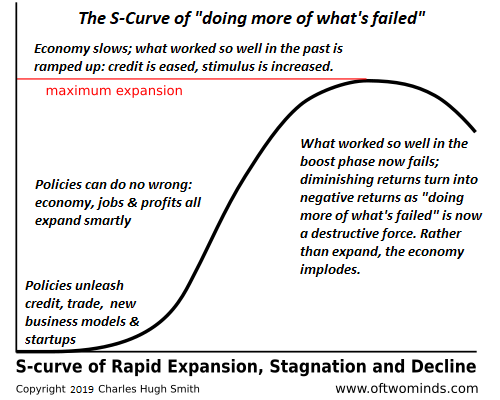

China’s model of economic development that worked so brilliantly in the boost phase, when all the low-hanging fruit could be so easily picked, no longer works at the top of the S-Curve.

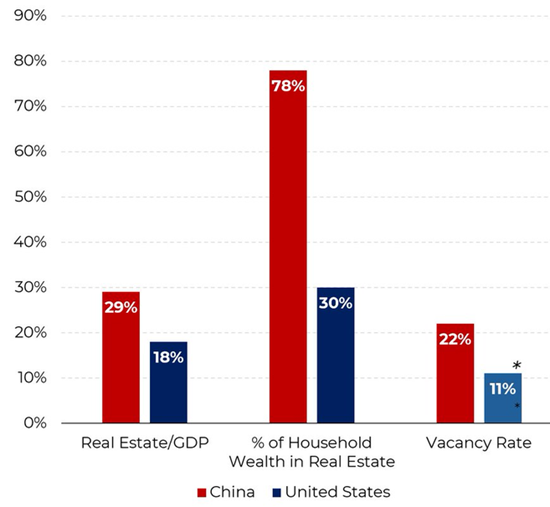

Having reached the saturation-decline phase of the S-Curve, these policies have led to an extreme concentration of household wealth in real estate. Those who favored investing in China’s stock market have suffered major losses. (see chart below)

This is the problem with overproduction as a model of endless growth: it eventually overwhelms demand and the income needed to pay for it.

Where China’s workforce was growing during the boost phase, now the demographic picture has darkened: China’s workforce is shrinking, the population of elderly retirees is soaring, and so the cost burdens of supporting a burgeoning cohort of retirees will have to be funded by a shrinking workforce who will have less to spend / invest as a result.

This is a global phenomenon, and there are no quick and easy solutions. Skilled labor will become increasingly scarce and able to demand higher wages regardless of any other factors, and that will be a long-term source of inflation. Governments will have to borrow more–and probably raise taxes as well–to fund soaring pension and healthcare costs for retirees. This will bleed off other social spending and investment.

The era of zero-interest rates and unlimited government borrowing has ended. As Japan has shown, even at ludicrously low rates of 1%, interest payments on skyrocketing government debt eventually consume virtually all tax revenues. Higher rates will accelerate this dynamic, pushing government finances to the wall as interest on sovereign debt crowds out all other spending. As taxes rise, households are left with less disposable income to spend on consumption, leading to stagnation.

At the start of the cycle, global debt levels (government and private-sector) were low. Now they are high. The boost phase of debt expansion and debt-funded spending is over, and we’re in the stagnation-decline phase where adding debt generates diminishing returns.

The era of low inflation has also ended for multiple reasons. Exporting nations’ wages have risen sharply, pushing their costs higher, and as noted, skilled labor in developed economies can demand higher wages as this labor cannot be automated or offshored. Offshoring is reversing to onshoring, raising production costs and diverting investment from asset bubbles to the real world.

Higher costs of resource extraction, transport and refining will push inflation higher. So will rampant money-printing to “boost consumption.”

The tech productivity boom was also a one-off. Economists were puzzled in the early 1990s by the stagnation of productivity despite the tremendous investments made in personal and corporate computers, a boom launched in the mid-1980s with Apple’s Macintosh and desktop publishing, and Microsoft’s Mac-clone Windows operating system.

By the mid-1990s, productivity was finally rising and the emergence of the Internet as “the vital 4%” triggered the adoption of the 20% which then led to 80% getting online combined with distributed computing to generate a true revolution in sharing, connectivity and economic potential.

The buzz around AI holds that an equivalent boom is now starting that will generate a glorious “Roaring 20s” of trillions booked in new profits and skyrocketing productivity as white-collar work and jobs are automated into oblivion.

There are two problems with this story:

1) The projections are based more on wishful thinking than real-world dynamics.

2) If the projections come true and tens of millions of white-collar jobs disappear forever, there is no replacement sector to employ the tens of millions of unemployed workers.

In the previous cycles of industrialization and post-industrialization, agricultural workers shifted to factory work, and then factory workers shifted to services and office work. There is no equivalent place to shift tens of millions of unemployed office workers, as AI is a dragon that eats its own tail: AI can perform many programming tasks so it won’t need millions of human coders.

As for profits, as I explained in There’s Just One Problem: AI Isn’t Intelligent, and That’s a Systemic Risk, everyone will have the same AI tools and so whatever those tools generate will be overproduced and therefore of little value: there is no pricing power when the world is awash in AI-generated content, bots, etc., other than the pricing power offered by monopoly, addiction and fraud–all extreme negatives for humanity and the global economy.

Either way it goes–AI is a money-pit of grandiose expectations that will generate marginal returns, or it wipes out much of the middle class while generating little profit–AI will not be the miraculous source of millions of new high-paying jobs and astounding profits.

What we now have is a hyper-centralized, hyper-connected (i.e. tightly bound), hyper-globalized and hyper-financialized global economy of extreme fragility, over-indebted and hollowed out by speculation, fraud, corruption, leverage, sclerosis and by an unbreakable addiction to doing more of what’s failed spectacularly.

The downside slide into recession and polycrisis-collapse is not as fun as the boost phase.

Concentrating assets, capital, control, debt and leverage also concentrates risk, which eventually leaks through the illusion of resilience and melts down the entire economy:

In a word, the global economy is toast. All that’s left is the distribution of the burned bits. Those who end up with collapsing currencies experience hyper-inflation, and those who manage to wallow in deflation experience stagnation as the best-case scenario. In all cases, the pool of creaky policies from the 1930s that will actually work has dried up: all the “fixes” that were solutions in the past are now accelerating the slide into a post-bubble recession with no visible exit.