by bitkogan

Sure, 3% is better than 9%. But given the new record highs in stock indices, it’s still not better enough to expect the Fed to start cutting interest rates anytime soon.

Firstly, 3% is still above the Federal Reserve’s long-term target.

Secondly, the low (relatively speaking) figures for the general consumer price index reflect a collapse in energy and food prices, with the core index still growing by almost 5%.

The story with energy companies is particularly interesting. It’s clear that, under normal circumstances, the faster their prices rise, the higher the overall inflation rate ought to go. Conversely, the cheaper oil and gas get, the lower the inflation.

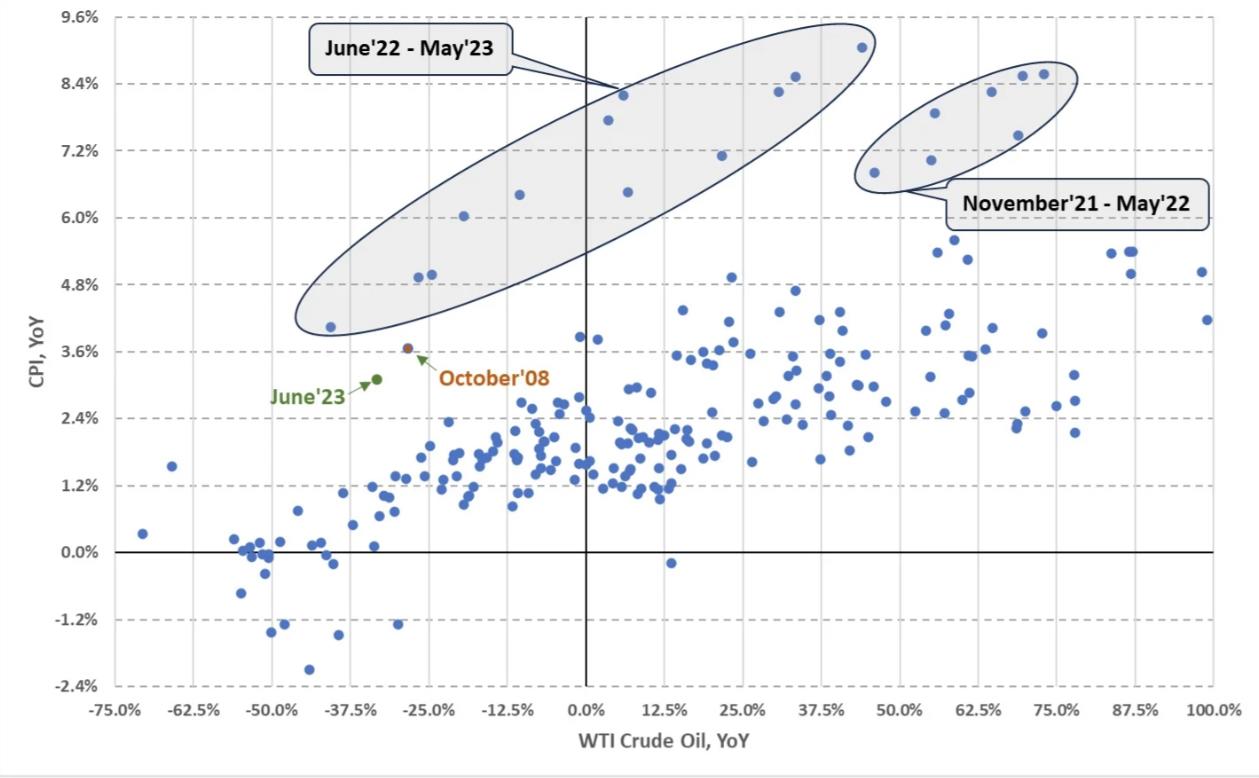

But if we compare the annual changes in oil prices and consumer prices in the U.S., we’ll see that the last year and a half clearly deviates from the previous 20 years of observation.

In 2008 and 2015, a drop in oil prices comparable to the current one sent the CPI to zero—or even below. In 2023, however, we’re still a seeing 3% rise. And even when oil prices were rising, consumer prices were growing faster than normal.

This is an inflation anomaly. The Federal Reserve, which probably won’t be in a rush to ease policy, sees it too. Such observation, of course, aligns with the remit of the regulatory body.

As long as the markets remain calm, Federal Reserve officials can continue to talk all but endlessly about the persistent risks to financial stability. They only start acting when high interest rates, and/or their own tough rhetoric, finally bring down stock indexes.

And just as a quick aside, the mutual dynamics of consumer prices and oil in the current century experienced a similar dynamic only once: in October 2008. That’s a risky parallel.