Authored by Charles Hugh-Smith via oftwominds,

I think it’s more productive to go with Plan B: set aside our emotions and reluctance and start doing the hard work of dealing with polycrisis.

A new reader kindly let me know that my writing was negative and depressing. I thanked the reader for the feedback and realized the question “why are you negative?” was a fair one that deserved an answer.

In a nutshell, the answer is the startling decay of everyday life. Why my writing strikes so many as negative is I am reporting from my direct experience and then pursuing a relatively simple query: do the institutions and systems that dominate our everyday lives have any formalized self-correcting mechanisms, and if so, why aren’t they working? If they lack such mechanisms, then they’re running to failure and this is not a positive outcome for all of us who depend on these systems and institutions.

Let’s stipulate a few things before we proceed.

1. If we can’t be honest, then why bother? If we can’t bear to face the visible, obvious realities in daily life, then what’s the point? If the real world I’m experiencing is instantly declared “negative and depressing,” then how do we actually make any progress? We can’t.

2. The secular religion of America is “you must always be positive, upbeat, and talk up hope.” A positive mental attitude is definitely a plus when compared to indignation, entitlement, resentment and passivity, but realistic appraisals are the essential foundation of actual problem-solving. Feeling inspired because “we’re going to Mars!” qualifies as upbeat but there is absolutely no connection between going to Mars and reversing the decay of our everyday life–none. The decay can’t be reversed by upbeat inspiration or some new gadget or app. The problems are far deeper and far more interconnected.

3. The source of hope is to face these realities directly rather than declare anyone who addresses them without sugarcoating a “doomer.”

4. The decay of everyday life is depressing because there are no easy fixes, and that there are no easy fixes is depressing, too. That’s part of the reality we wish to avoid. But that doesn’t mean there are no ways to improve the situation, and the path to improvements, both systemic and personal, are what I write about.

5. We all need a break from depressing realities. I strictly limit my exposure to the media and social media as an essential means of retaining some shred of sanity. I focus on the real world, and the workings and consequences of the systems we rely on.

6. Where you stand matters. Many of my readers are older, and therefore likely to have bought a nice home for $45,000 decades ago at the start of their careers, worked hard, earned a pension or accrued a 401K fattened by the relentlessly rising stock market and are now worth $2 million. From where they stand, life in America looks good, and focusing on the decay of everyday life somewhere other than their neighborhood strikes them as negative and depressing.

7. Abstractions don’t reverse the decay of everyday life. Waving a chart of the GDP around–it’s rising, so everything’s great!–has no connection to real-world decay or institutional dysfunction. That household wealth rose $20 trillion doesn’t means the problems are magically going away on their own; it simply means the system is optimized to make the already-rich richer. Waving a chart of GDP around doesn’t actually solve anything. It’s the functional equivalent of waving photos of cute kittens and puppies around and saying “everything’s going great!”

8. All this is evidence that we’re losing the will to actually reverse decay and are choosing to change the narrative as the “solution”. In other words, if we stop talking about the negative, depressing decay of everyday life, then we can get on with being upbeat and positive–look at GDP and household wealth, they’re going up! This desire to change the narrative rather than actually tackle difficult problems is understandable, but fatal to actual problem-solving. It is the equivalent of the Roman upper class reassuring themselves that Rome was eternal, so everything would sort itself out on its own because it had always been sorted in the past.

Here’s my direct experience in the real world: a 21-year-old today cannot have what I had 50 years ago: a part-time job that paid for my college tuition and books, a studio apartment, ownership of a car and spending money. I didn’t have to borrow a dime to work my way through college, have my own apartment and car and have a life beyond classes and work. I have documented this in detail: We Feel Poorer Because We Are Poorer: Here’s Proof (December 4, 2023).

Let’s not over-complicate what’s straightforward: we’re becoming more prosperous when our wages / labor buy more goods and services, especially the essentials of life: shelter, food, energy, utilities, transportation, higher education, healthcare and childcare. If the money we have left after paying for essentials buys more discretionary goods and services, we’re getting more prosperous.

If the essentials are consuming a greater percentage of our earned income, we’re becoming less prosperous, i.e. we’re poorer. Those tasked with persuading us that gradual impoverishment is actually soaring prosperity have near-infinite statistical means to obscure this straightforward measure of prosperity: the purchasing power of labor / earnings.

If our hours of work buy fewer goods and services, we’re getting poorer.

Fifty years ago, tuition at a four-year state university was $233 a year. That’s about $1,400 in today’s dollars. Today, the tuition at my alma mater is $14,500, a ten-fold increase. The same goes for rent and other expenses. If wages for 21-year-olds had risen by more than ten-fold, then everyday life would actually have improved. But this simply isn’t the case.

I could afford my own small studio apartment, an old car and some spending money and pay all my tuition, fees and books out of my part-time earnings. Granted, I was frugal and made more than minimum wage, but still–what I did was not impossible or unusual. Yes, it required working a lot of hours but it was certainly within reach. (I lived in Honolulu, one of the most expensive cities in the U.S. It would have easier virtually anywhere else.)

Can anyone claim this is true today with a straight face? If it’s true, then show me by doing it yourself. Go get a job at the same wages paid to a 21-year old, work fewer than 30 hours a week, and then rent your own flat, pay for your own car, pay all tuition and fees at a four-year state university and have a bit left over for the occasional bowl of ramen or movie or saving for a vacation.

If it’s still within reach, then why isn’t it the norm of everyday life for 21-year-olds today as it was two generations ago? If we’re honest–and we’re still able to be honest, aren’t we, or have we lost that, too–then we have to admit this isn’t progress, it’s the opposite of progress: life is harder now, not easier.

That cars have rearview cameras and apps do this or that and now we have electric cars–none of these reverse the startling decay of affordability, purchasing power and thus prosperity.

Here’s my direct experience in the real world: America is awash with refugees from what must be a great conflict or natural catastrophe. We call these refugees “the homeless.” I lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for 32 years. Tech capital of the world, beautiful people, scenic, nice weather, home to the smart, ambitious, wealthy, and so on.

Around eight years ago, empty stretches of roadways suddenly filled with dozens of vehicles–encampments of the homeless. Patches of lawn near freeway offramps were suddenly filled with tents and trash. A tent encampment arose a block from our house–not in a “bad neighborhood,” just not a protected enclave in the hills.

A homeless individual–does it really make us feel better to call this person “unhoused”?–started sleeping right beneath our bedroom window. I had to hose human excrement off our somewhat sheltered (and therefore ideal to use as a toilet) front entry. (We moved away in early 2019. Some solutions are systemic, some are individual initiative.)

Charts of GDP–it’s going up!–aren’t really relevant when you’re hosing human excrement off your front porch. Neither are rising sales of EVs–we’re saving the planet by stripmining it to make two billion unrecyclable batteries! These are abstractions, and they do nothing to reverse the startling decay of everyday life.

What caused this enormous flood of domestic refugees? We like simple answers and simple solutions, but there aren’t any. The unaffordability of essentials such as shelter are certainly a factor, but the decay of family, social ties and the economy all play a part.

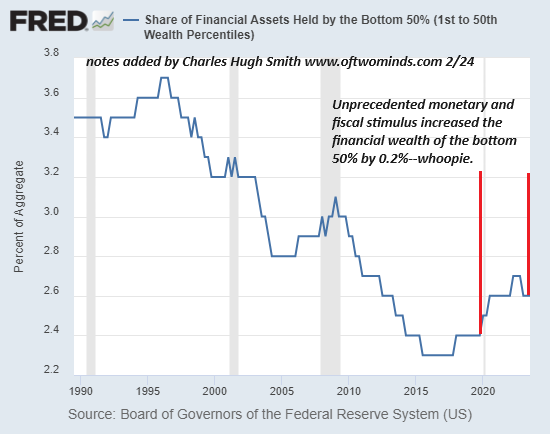

How can we claim with a straight face that “life is getting more prosperous” when half the populace owns essentially zero financial wealth? Trillions in stimulus has piled up tens of trillions in financial wealth, but how has so little trickled down to the 170 million Americans who comprise the bottom 50%? Can we declare “this is an increasingly prosperous nation” after pondering this chart? That 170 million Americans own a grand total of 2.6% of the nation’s enormous financial wealth? That’s statistical noise, not prosperity.

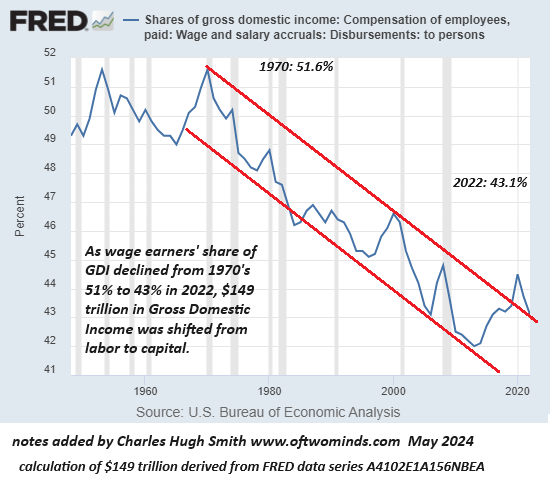

Yes, this is negative and depressing. Why? Because it’s fact, and there are no easy, one-size-fits-all fixes. If we’re looking for a conflict or natural disaster that unleashed a massive reversal of progress, we might want to look at how wages have fared versus capital: capital skimmed $149 trillion from wage-earners.

Here’s my direct experience in the real world: the quality of appliances and other everyday life products has declined precipitously. My first apartment in the SF Bay Area in 1987 had a 40+-year old refrigerator, still humming along. In the early 1990s, a neighbor gave us his old 1960s era fridge when he bought a new one. The point here is that appliances routinely lasted 30 or even 40 years two generations ago, and now they fail within a few years.

This is not an abstract data point like GDP or federal debt. This is the real world. I have personally replaced the motherboard in a name-brand dryer that failed in a few years. The plastic part had a few cheap circuit boards and commodity chips, total value $20 at the most, and it cost $180 plus shipping. Add in labor (if I hadn’t been able to do the task myself) and the cost equaled the price tag of a new dryer.

Our name-brand washer and fridge both expired within the last year after less than a decade of service. If you talk to the staff in a big-box appliance department, they’ll tell you 7 to 8 years is about the norm now. In many cases, that’s not reality. We have many firsthand reports from family and friends of expensive, fancy fridges failing within three years.

Is this progress? No. The collapse of durability and quality is a catastrophic decay of progress and prosperity. Waving charts of GDP or photos of rockets doesn’t reverse this decay of everyday life.

Here’s my direct experience in the real world: a building permit that once took a day to issue now takes six months. Same basic plans for a modest starter house as forty years ago when I dropped the plans off in the morning and picked them up, stamped and approved in the afternoon, so what changed?

It’s certainly not the way houses are built. That hasn’t changed enough to affect the permit process. What changed is the functionality of the institution issuing the building permits. The functionality has fallen off a cliff. This is not progress or prosperity. It is a startling decay of everyday life.

Is declaring the real world negative and depressing part of a productive problem-solving process? I don’t think so. I agree that knotty, interwoven problems are difficult to tease apart and reverse. Many of these problems are embedded deep inside institutions, where they are difficult to see.

What I write about are solutions, but to write about solutions first requires making realistic assessments of the problems. That we respond to difficult problems by feeling they’re negative and depressing is understandable. But we have a choice: do we follow the elite Romans in placing our faith in the comforting idea that difficult adaptations made in the past will magically manifest now without us having to do anything? Or do we set aside our emotions and reluctance and start doing the hard work of dealing with polycrisis?

I think it’s more productive to go with Plan B: set aside our emotions and reluctance and start doing the hard work of dealing with polycrisis. I am hopeful about reversing the decay of everyday life, and I’ve written books about how to do so. But please don’t think that waving charts of GDP or EV sales is doing anything other than distracting us from the tasks at hand.