by Chris Black

Even as demand for labor continues to increase with economic growth, the supply of labor in the U.S. is stagnate absent ever larger wage increases.

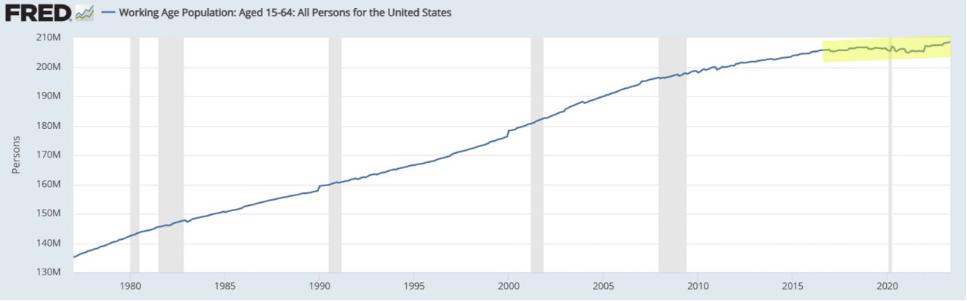

The working age population of the U.S. plateaued a few years ago (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LFWA64TTUSM647S), so increases in labor supply have largely come from attracting those outside the work force using high wages.

At the same time, demand for labor appears to persist with steady economic growth and a growing population of retirees.

This post sketches out the overall supply & demand dynamics of labor , and suggests persistent economic growth could lead wage growth (and inflation) to re-accelerate amidst structural labor scarcity.

Labor Supply

The U.S working age population has stagnated for several years , so marginal increases in workers have largely come from higher labor force participation rates.

Fertility rates in the U.S. began to steadily decline in the 1960s (https://archive.is/Yi9UC) and have, broadly speaking, been below replacement levels since the 1970s.

The impact of that decline is now being felt in a working age population that has shifted from steady growth to stagnation since around 2016.

Net immigration has contributed to some recent growth, but overall has been relatively small at around one million migrants (https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/12/net-international-migration-returns-to-pre-pandemic-levels.html) each year for the last decade.

Marginal increases in the supply of labor have largely come from encouraging greater labor force participation with higher wages.

The pandemic was a significant negative labor supply shock because it led to a wave of early retirements (https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2023/jun/excess-retirements-covid19-pandemic), which can be seen in the sudden drop in the labor participation rates of those aged 55 and above.

This sudden labor shortage led to a spike in wages (https://www.atlantafed.org/chcs/wage-growth-tracker), which appeared to draw in people who were otherwise not looking for a job.

The prime age labor force participation rate has risen to multi-year highs and is not too far from all-time highs last seen in the 1990s.

This suggests that there is very little slack in the labor market and additional workers will be increasingly difficult and expensive to find.

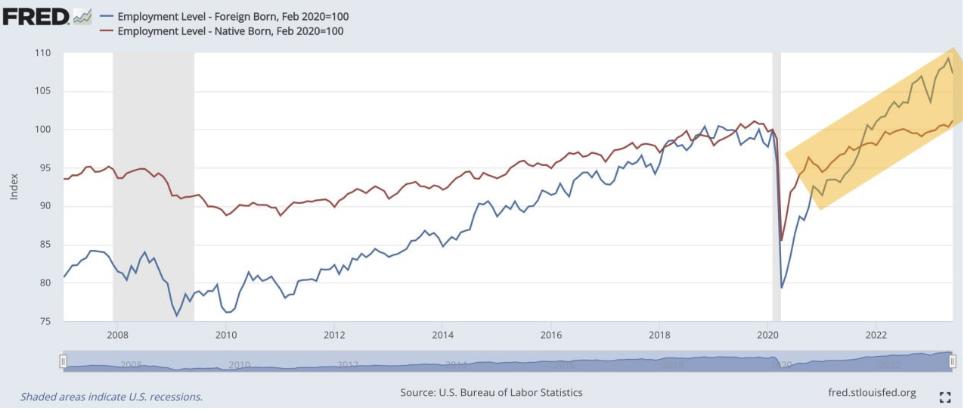

Clearly, per the FRED chart , immigrants have provided a marginal supply of labor post-pandemic.

Labor Demand

Steady U.S. economic growth and an aging population suggest that demand for labor will continue to grow for the foreseeable future.

The U.S. economy most recently grew at 2% (https://www.bea.gov/data/gdp/gross-domestic-product), which is above the Fed’s 1.8% estimate (https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20230614.pdf) of trend growth.

Recent forecasts (https://www.atlantafed.org/cqer/research/gdpnow) point towards continued growth, which can also be seen in the steady number of jobs (https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm) created each month.

While interest rates have risen significantly, monetary policy does not appear to be very effective (https://fedguy.com/its-not-working/) at slowing demand.

This may be in part be because fiscal spending remains robust (https://www.marketwatch.com/story/u-s-budget-deficit-surges-in-may-and-tops-1-trillion-again-in-current-fiscal-year-cf025cda) and household wealth levels remain high (https://fedguy.com/excess-wealth/).

Demand for labor is also likely to grow from a rising age dependency ratio , where each worker must support an increasing number of retirees. Although retirees no longer work, they continue to consume goods and services.

Some research (https://www.bis.org/publ/work656.pdf) even suggests that overall consumption actually rises in retirement due to greater use of medical services.

Social security data suggest that the retiree population is growing at a rate of around 3 million people a year.

Given a stagnant working age population, increasing retirees means that demand for their labor is set to continue to grow.

Two Views

The labor market data thus far permit readings that are supportive of both slowing demand for labor and growing labor scarcity.

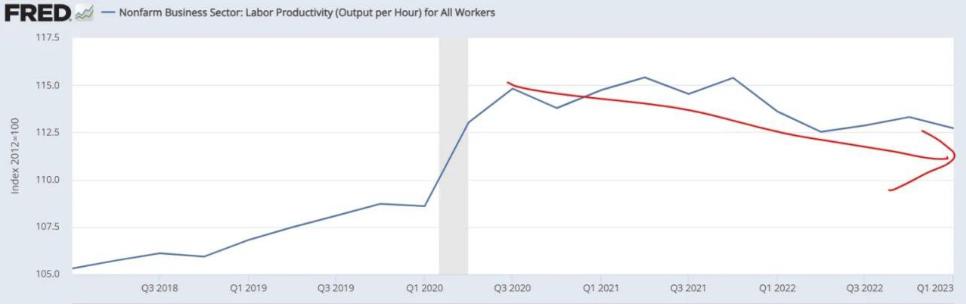

Over the past several months there has been slower growth in employment, lower productivity, and moderating wage growth.

In prior cycles this would easily be interpreted as a slowing economy leading to less demand for labor, with declining productivity potentially due to a shift to remote work. But demographic shifts also make labor scarcity a plausible explanation.

Recent employment data could also indicate a moderating of the pandemic retirement shock and resumption towards structural labor scarcity.

The sudden loss of millions of workers led to a spike in wages that drew in marginal workers with weaker skills that lowered aggregate labor productivity.

While that shock has been digested, workers continue to retire and place increasing demand on a stagnant worker pool.

In this scenario, moderating employment growth reflects labor scarcity and would be accompanied by reacceleration of wages, similar to what the most recent non-farm payroll report suggested (https://t.me/marketfeed/422864) is happening.

That would equate to a reacceleration of inflation, and would predictably be a nightmare scenario for the Fed.

306 views