Authored by Charles Hugh-Smith via oftwominds,

There are no more “saves” available for the next market meltdown.

The past 24 years can be viewed as an era in which risk declined due to the dynamics of globalization and financialization.

The ascent of China as “workshop of the world” generated a deflationary wave of lower prices for products (due to lower labor costs and lower quality components) that blunted the inflationary impact of the global economies adding $150 trillion in debt since 2000. Global debt, public and private, now tops $315 trillion, 333% of global GDP.

Absent the deflationary impact of globalization, this vast increase in money sloshing around would have sparked inflation. Absent the vast expansion of money via financialization, the expansion of production and consumption enabled by globalization could not have occurred.

At the same time, central banks coordinated policies to steadily reduce interest rates, reaching effectively zero or negative rates (when adjusted for inflation) in 2009 and beyond. This reduction of rates far below historic norms enabled creditors to borrow more even as their debt service costs fell.

Financialization vastly increased leverage and the commodification of credit/debt, enabling emerging-market nations and enterprises and consumers globally to increase their borrowing/spending.

Globalization generated incentives for nations and their central banks to “play nice” and cooperate with other governments and banks to spur profitable (and happily deflationary) trade. These coordinated efforts enabled the global economy to avoid the potentially fatal disruptions of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008-09.

Despite localized droughts and extreme weather, global food production increased by expanding land in production and intensifying agricultural methods.

All of these risk-reducing trends are reversing or reaching diminishing returns.

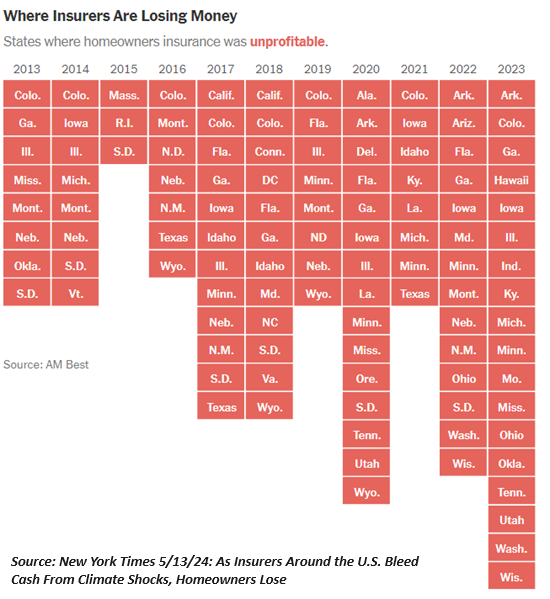

Extreme weather events are increasing, leading to massive losses by insurers, a trend described in As Insurers Around the U.S. Bleed Cash From Climate Shocks, Homeowners Lose (New York Times)(seechart below):

“In 2023, insurers lost money on homeowners coverage in 18 states, more than a third of the country, according to a New York Times analysis of newly available financial data. That’s up from 12 states five years ago, and eight states in 2013. The result is that insurance companies are raising premiums by as much as 50 percent or more, cutting back on coverage or leaving entire states altogether. Nationally, over the last decade, insurers paid out more in claims than they received in premiums, according to the ratings firm Moody’s, and those losses are increasing.

The growing tumult is affecting people whose homes have never been damaged and who have dutifully paid their premiums, year after year. Cancellation notices have left them scrambling to find coverage to protect what is often their single biggest investment. As a last resort, many are ending up in high-risk insurance pools created by states that are backed by the public and offer less coverage than standard policies. By and large, state regulators lack strategies to restore stability to the market.”

Much of the rising cost is a result of global insurance losses, which boost the reinsurance rates insurers must pay to cover the risks of extreme events generating extreme losses that push insurers into bankruptcy. Hawaii insurance chief doesn’t see carrier exit as costs rise:

Reinsurance is something insurance companies buy to cover extraordinary losses, and it is part of a policy’s price. This reinsurance cost, which is tied to the global insurance industry, has increased 20% to 50% annually during the past several years, according to Ito.

“The cost to insure homes or condos is going up because of this tremendous surge in the reinsurance costs,” he said.

Ito said there were 23 climate-related disasters in the United States in 2023 that caused at least $1 billion in losses, and that in five of the past six years, the reinsurance industry incurred losses of over $100 billion worldwide.

“Reinsurance is worldwide,” he said. “Events that happen in Europe, or in Asia, or in Kansas, or in Florida, all impact the cost of reinsurance that insurers pay regardless of where they write business.”

The rising costs of insurance reflect a critical dynamic of risk: in a tightly bound, interconnected global system of finance and trade, risks arising anywhere in the system increase costs and risks throughout the system.

This is the downside of increasing our dependence on tightly bound global systems to lower prices: disruptions and risk now spread rapidly to every node and participant in the global system: events far away trigger the cancellation of your insurance policy or an astounding increase in its cost.

What were beneficial in the low-risk growth phase–increasing dependence on global capital and trade flows to lower prices and boost borrowing–are now sources of rising risk–risk that cannot be fully hedged even as the cost of hedges such as insurance rise sharply.

Let’s consider the other dynamics turning a low-risk era into an unstable, high-risk era.

Our starting point in an examination of risk is the nature of the global system we are dependent on / embedded in. The dominant economic model in this system is “the market,” an idealized construct in which buyers and sellers “discover the price” of everything from currencies, risk, goods, services, labor and capital, and any scarcities are filled by new production (as people rush to reap higher profits by expanding production) or substitution (beef too expensive? Replace it with chicken).

This construct creates a happy illusion: the system operates as a closed system in which all the moving parts are visible and measurable. This creates the illusion that the system is inherently self-correcting and therefore stable, as buyers, sellers, producers and consumers all pursuing their own self-interests will maintain what’s known as dynamic equilibrium: prices may spike or collapse for a short time, but the system will quickly adapt and equilibrium will be restored.

The real world is not a closed system in which all the moving parts are visible and measurable. The real world is an open system operating not solely by the pursuit of self-interest but by natural selection unguided by any goal or destination.

We presume “Progress” has an inherently upward trajectory: everything inevitably gets better as technology advances. In other words, we view the dynamics of history and Nature as teleological: they are on a path heading toward a goal.

This is a misunderstanding of Nature. Natural selection has no goal. If external changes disrupt an ecosystem, some species may be wiped out. From their point of view, this was not inevitable progress toward a goal.

The tightly interconnected global system is akin to an ecosystem. It is an unpredictable, unstable open system, not a predictable, stable market. External events can lead to scarcities for which there are no substitutes or increases in production, and irreplaceable links can be broken, collapsing the system beyond repair.

When the Vandals wrested the North African wheat production away from Roman control, the Roman Empire lost the primary food source feeding the half-million residents of Rome, many of whom were granted a free bread stipend–hence the term “bread and circuses.”

Since there was no substitute for this lost wheat, and the residents grew little or no food themselves, the result was the collapse of the entire structure. (There were other factors, of course, such as the unaffordable cost of maintaining a paid mercenary military, pandemics, etc.–what we now call a polycrisis.)

The point here is risk is often hidden in systems that are stable for long periods of time. It isn’t non-existent; it is simply out of sight. This conditions us to believe that the system is self-correcting, and so we become complacent.

A recent example of this is the way the Federal Reserve and other central banks have “saved” the stock market every time it stumbled for the past 15 years, since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09. We’re now conditioned to “buy the dip” because every time the market dips, the banks leap into action and markets soar to new highs. This is like clockwork, and so only fools doubt that the next dip will also be “saved” and markets will once again soar to new heights.

In the context of global risk, “buying the dip” appears to be low risk. But this conditioning / complacency overlooks the fact that China “saved the global financial system” by rapidly expanding its own debt load, what we call “leveraging up” debt, much like a homeowner with a modest mortgage and plenty of home equity can borrow against that equity, leveraging the collateral into much higher debt loads.

China is now mired in the same slow-growth, over-indebted, property-bubble, rising inflation, decaying global trade environment as every other nation which precludes it “saving the world” again.

Now that the deflationary impulse of rising global trade has reversed, there’s nothing to counter the inflationary pressures generated by the decay of globalization and financialization: interest rates cannot be pushed back down to zero, as that will only boost inflationary forces. Since collateral has already been “levered up,” there’s no more pool of collateral to support a new credit bubble.

Should central banks attempt to “save the market” by dropping interest rates to zero, that won’t boost borrowing and spending because the system is already over-levered: staggeringly large sums of debt are already unsupported by collateral, for example, commercial real estate in the U.S.: buildings that sold for $200 million a few years ago are now entering foreclosure and being auctioned off for $10 million or less. The underlying value of the property–the collateral supporting the loan–has collapsed.

In other words, there are no more “saves” available for the next market meltdown.

Another systemic source of risk was described by Benoit Mandelbrot in his book The (Mis)Behavior of Markets. (The book’s original 2004 subtitle was “a fractal view of risk, ruin, and reward.” The current edition’s subtitle is “A Fractal View of Financial Turbulence.” I prefer the original subtitle, which is more to the point: risk and ruin.)

In the conventional view of risk / portfolio management, “100-year floods” occur, well, every 100 years or so. This risk of such a devastating disaster occurring in any one year is thus low.

But as Mandelbrot explained, these catastrophic floods don’t occur every 100 years–they occur every 5 years or so, as the mathematical models used to ascribe risk are deeply flawed. Nature is fractal, and thus prone to sudden instability.

Nassim Taleb explored the nature of unpredictable/improbable risk in his book The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable.

The decades of relative stability between 2000 and 2020 conditioned us to complacently believe the global system was now so robust and our stabilizing institutions (central banks) so powerful that risk was if not banished, manageable and could be readily hedged.

This is not realistic, and so we’re ill-prepared for shocks to the system that fatally destabilize trade and capital flows we assume are permanently dynamically stable, i.e. any spot of bother will be corrected by one institution or another.

Another systemic source of risk is the thinning of systemic buffers is not visible. In other words, the rising risk of instability is invisible to us as long as the system appears to be functioning normally. So we’re surprised when fisheries collapse, ground water dries up, financial systems implode, and so on, because everything appeared to be more or less the same.

We can view the human body as a metaphor for the way a system attempts to maintain homeostasis / equilibrium, but the effort required overtaxes the systems tasked with correcting / rebalancing the entire system. The individual feels “normal” and has no awareness of rising risk until they experience a cardiac arrest or their metabolic disorder strikes them down.

Risk is slowly being repriced globally, as costs rise and trade and capital dependencies undercut stability. What we currently view as predictable closed systems will be revealed as unpredictable and potentially destabilized open systems that cannot be restored to previous forms of stability.

How do we operate in a world in which risk cannot be fully hedged, and apparently small events can collapse critical systems on which we’re dependent? The first step is to set aside conditioning that leads to complacency and false assumptions of safety / stability. The second step is to mitigate risk before it rises up like a tsunami: reduce debt, exposure to financial risks, reduce our dependency on global, tightly bound interconnected systems, move to places with a diversity of essentials, and invest in our own self-reliance. I wrote my book Self-Reliance in the 21st Century as a general guide to this de-risking process.

174 views