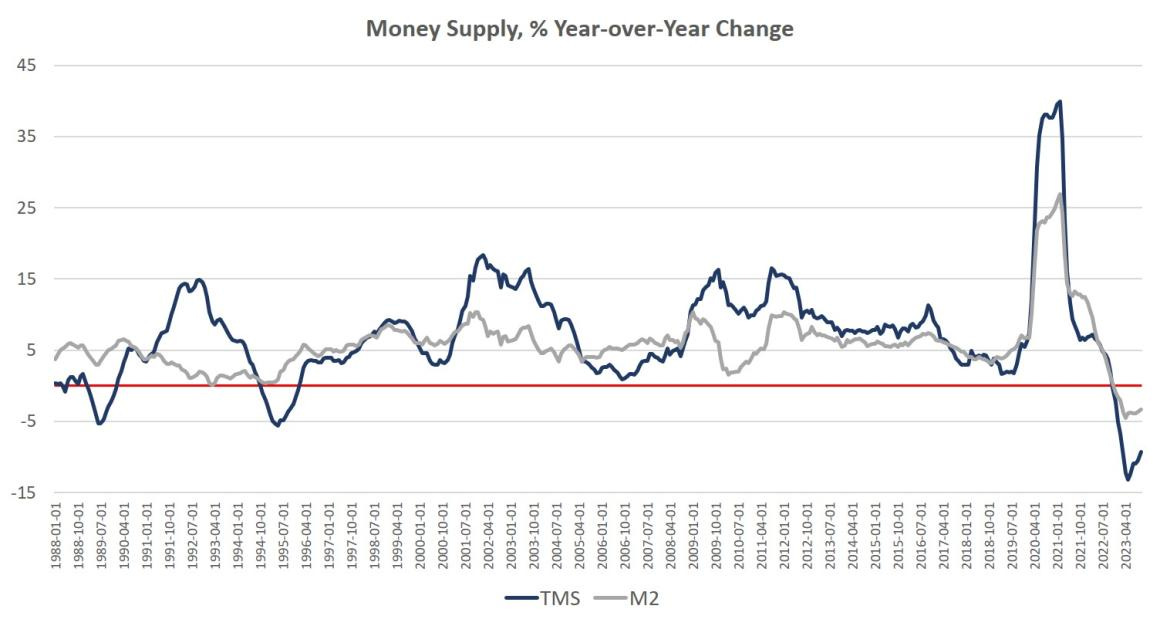

Evidence of a severe recession that has already begun continues to build, and the cause is clear. As you can see in the following graph, money supply fell again in October and its “growth” has, during the Fed’s current quantitative tightening (QT), gone negative, since the end of last year, for the first time in almost three decades.

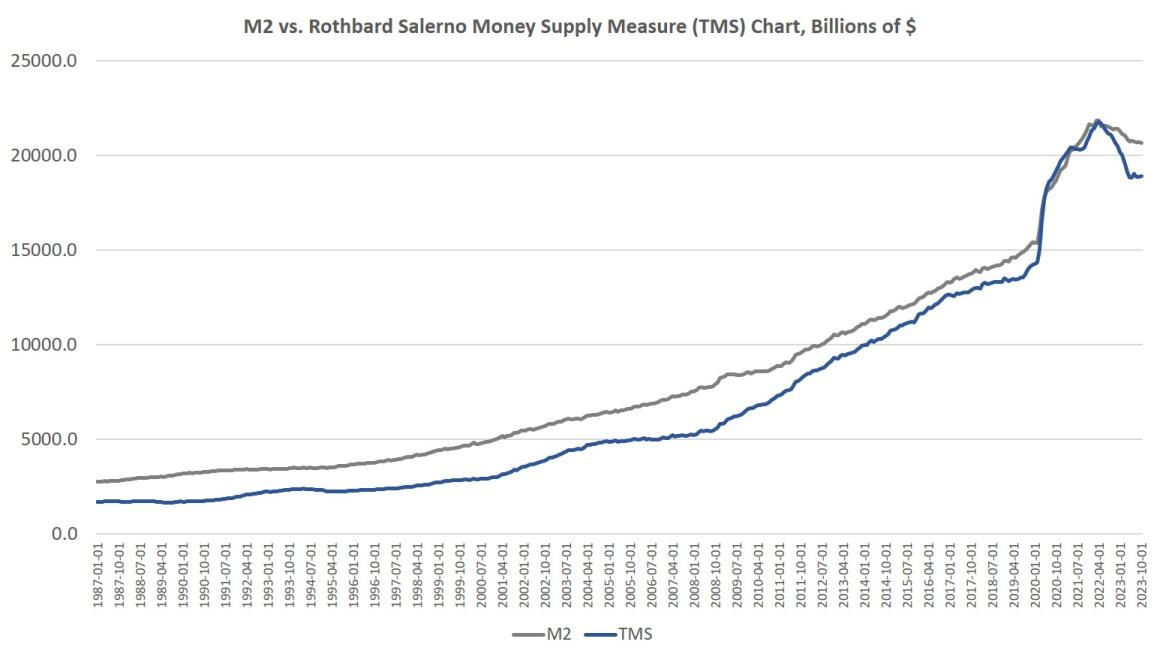

During earlier periods of Fed tightening, money supply growth has slowed way down, but it has never actually shrunk since 1994-1995. Even during the Fed’s strenuous QT of 2017-2019, money supply continued to grow as can be seen in this graph:

The first graph shows the rate of growth; the second shows the effect of that growth rate on total money supply. You can see that under the Fed’s interest hikes in 2017 and its QT from the end of 2017 into 2019, money supply continued to grow at a good clip, but just not as rapidly as it had been rising during years of QE (quantitative easing) . The smaller decline into “negative growth” in the nineties is barely even visible as a dip on the graph of total money supply. Likewise with the “negative growth” dip in ‘89. Yet, the present decline is more of a plunge than a dip.

(Note that interest hikes have the same effect on taking down the growth rate in money supply as QT has because money is created in the global economy that runs on the US dollar by banks making loans where money doesn’t exist. They create the more through the loan because they are allowed to highly leverage the deposits they have when they make loans, loaning out many times more money than what they have on deposit. That is how NEW money is created out of thin air — by the banks. The Fed’s QE just raises bank reserves, not money supply directly; however, lifting those reserves allows banks to make more loans to whatever extent the Fed allows them to leverage those reserves. Higher interest results in less demand for loans, so slows the rate of growth in money supply, but it doesn’t subtract money. Only QT can suck money out that already exists, taking “growth” negative as we now see.)

Yet, that quantitative tightening in 2017-2019 resulted in a year-long stock market crash that came in phases throughout 2018, but took the stock market negative by year end, and its continuance into 2019 gave us the Repo Crisis of late 2019. You can see a tiny little bump in money supply at the end of 2019 when the Fed reversed QT and went back to QE to end the Repo Crisis by rolling over endless “overnight loans” of more than $100-billion that failed to resolve the Repo Crisis until the Fed went parabolic with money printing during the Covid Crisis in 2020 where it could no longer keep claiming it was “not QE.”

So, all that trouble came from QT that didn’t even bring money supply down. It merely slowed its growth. Now, however, we see money supply actually going down a lot. And we know that Fed actions generally have a long lag effect. Some say 6-8 months. Others claim 12-18. The first would be about right for when a change in Fed monetary policy begins to show its effect, and the latter range is more likely correct for when the policy change stops causing additional economic effect.

If a mere slowdown in the growth of money supply caused such upheaval in 2018 and 2019, what will the huge drop we see today cause before it is all said and done? Before you answer that, consider that the current drop into “negative growth” in money supply is actually the deepest since the Great Depression. (The information source here is the Mises Institute from an article linked to in the headlines below.)

In yesterday’s editorial, I wrote about how the repo market is, again, fluttering, indicating the effects of so much tightening may be starting to cause tightness in the market where banks loan to each other and to hedge funds — areas where considerable trouble from QT and interest hikes has emerged in the past.

Not too surprisingly, actual drops in money supply tend to be associated with bad recessions:

Money supply growth can often be a helpful measure of economic activity and an indicator of coming recessions. During periods of economic boom, money supply tends to grow quickly as commercial banks make more loans. Recessions, on the other hand, tend to be preceded by slowing rates of money supply growth….

Recessions are often preceded by a mere slowing in money supply growth. But the drop into negative territory we’ve seen in recent months does help illustrate just how far and how rapidly money supply growth has fallen. That is generally a red flag for economic growth and employment.

Of course, we know, from what we experienced during the Fed’s last QT, that QT didn’t cause a drop in money supply at all, but just a slowdown in the growth of money supply. It’s no wonder, then, that the surface of the repo market is now fluttering and that banks went bust earlier this year when an actual drop in money supply gained speed.

Now, you might rightly note that money supply needs to drop by a lot since the Fed went crazy creating such a huge and ridiculous expansion, and you might even be inclined to think this just takes us back to normal —- removes the expansion — EXCEPT that the expansion of the economy after the 2020 Covidcollapse, forced by the governments of this world under world health orders, has been highly dependent on that extreme monetary largesse all along. We’re about to find out how badly the real economy functions on its own without all that surplus life support to keep it looking “in the pink.”

When the patient shows proper color only due to extreme life support pumping blood through his arteries and only remains alive through years of sustaining that life support, then removal of the long sustained life support bodes poorly for what happens next. It’s called “pulling the plug.” Think of what happens when the patient has also developed a drug dependancy. If the patient has developed a dependency on a particular drug, taking the drug away causes withdrawal.

So, today we see a little more slowdown in the labor market (withdrawal) among the headlines below, and we see the stock market faltering again as it digests what these labor reports mean in terms of the Fed continuing to take down the market’s drug supply. This patient has been addicted to multiple drugs for a period of about thirteen years, so how much upheaval will removal cause after that much time of total dependency?

Nonetheless, the monetary slowdown has been sufficient to considerably weaken the economy. The Philadelphia Fed’s manufacturing index is in recession territory. The Leading Indicators index keeps looking worse. The yield curve points to recession. Temp jobs were down, year-over-year, which often indicates approaching recession. Default rates are rising.

The economic malaise is setting in. Consider that life support has been massive beyond anything experienced prior to this new millennium through four major rounds of QE, the largest of which came after Covid, and none of those rounds ever got fully removed before troubles emerged. Not even close. Yet, the Fed plans to continue draining via QT indefinitely, even after it stops raising interest rates and just holds them high until it is certain its battle with inflation is over.

Do you think we have any chance of that happening without a dire recession or, alternatively, avoidance of that deep recession by turning back to full-on QE as the Fed had to do in all past times … except that in none of the past times did the Fed have high inflation to wrangle with that would be made worse by a return to money printing. The Fed cannot back out of these troubles it is creating as it did so facilely when past periods of tightening failed without reigniting inflation.

It is in that sense that I have said throughout QE the Fed had no end game that would ever work. We’ve seen each end game it has tried FAIL, including when it merely stopped early rounds of QE and had to suddenly administer even larger rounds to end the damage that came with stopping.

From the beginning, dependency on QE meant the Fed was painting itself into a corner where it is trapped into creating endlessly massive money supply to sustain the economy that the Fed is making dependent on loose money (bubble economies). The Law of Diminishing Returns. I’ve noted all along the way that has meant the next round of QE needed to be bigger to get any result. The bubble has increased from one big one in 2007 to several big ones, and then the bubbles have expanded into hot-air balloons to keep lifting the economy. In fact, rather crazy-looking ones like this monster:

But the balloons are descending as the hot air comes out with QT or cools with interest hikes. Bankruptcy filings under the past year of QT and interest hikes have risen 21% over where they were at this same time last year. That increase is roughly the same among both businesses and individuals for all types of bankruptcy.

There was a better path than the one we now all have to pay for through a massive deflation of all the balloon or pay for forever through the endless sustaining of high bubble inflation to keep the balloons aloft with more hot air so they don’t settle:

If the Fed reverses course now, and embraces a new flood of new money, prices will only spiral upward. It didn’t have to be this way, but ordinary people are now paying the price for a decade of easy money cheered by Wall Street and the profligates in Washington. The only way to put the economy on a more stable long-term path is for the Fed to stop pumping new money into the economy. That means a falling money supply and popping economic bubbles. But it also lays the groundwork for a real economy—i.e., an economy not built on endless bubbles—built by saving and investment rather than spending made possible by artificially low interest rates and easy money.

You might look at it this way as reported in another article:

U.S. stocks retreated on Wednesday as investors assessed data indicating falling inflation, while the jobs report loomed.

You’ve got your choice, high inflation that stays high or falling jobs in a moribund economy. The lag effect is now over, and jobs, according to today’s report, are continuing to fall away. As I’ve noted a few times, it only takes a rise of 0.4 points in inflation to trigger immediate recession at that point, and we just hit that number.

“ADP’s payroll data shows the Fed’s anti-inflation treatment is now really taking effect,” said David Russell, global head of market strategy at online investing platform TradeStation. “The numbers point toward a soft landing, but investors may start to worry about a recession if policy remains too hawkish. It’s the Fed’s battle to lose at this point….”

Obviously, he hasn’t paid any attention to that money-supply graph, which shows the largest revision in money supply since the Great Depression, or he wouldn’t be banking so comfortably on a soft landing. What we’ve felt so far is merely the beginning tremors of that huge and ongoing plunge in money supply. Add another year after whatever the date is when the supply stops shrinking for its effect to stop building.

On Tuesday, Labor Department figures showed job openings in October fell to the lowest level since March 2021….

The declines raised questions around whether the late 2023 rally was taking a pause or if the market had run up too far, too fast.

You know my answer to that. It has run up well beyond all sensibility based on the numerous months we have left for Fed policy to continue to play through now that it has started showing up. Those get added to the months that the Fed continues to drain money supply through QT, making the situation worse, which also have a lag effect and which the Fed has said it has no intention of ending anytime soon because, well, QT will, as former Fedhead Yanet Jellin’ has assured us during the past failed attempts, “be as boring as watching paint dry.”

Maybe as boring as watching paint dry from a fluttering balloon that is still 10,000 feet in the air but out of fuel to keep reheating its own air. That probably doesn’t land too softly.