Those seeking to buy a house as shelter for their household can’t compete with the wealthy seeking assets to snap up and hoard for appreciation.

Longtime readers know I’ve been addressing housing issues from the start of the blog in 2005. Let’s start with the general context of housing in the US, courtesy of the US Census Bureau, which tracks occupancy and the number of housing units nationally: Quarterly Residential Vacancies and Homeownership, 4th Quarter 2023

All housing units 145,967,000

Occupied 131,206,000

Owner 86,220,000 59%

Renter 44,985,000 31%

Vacant 14,761,000 10%

Non-seasonal (i.e. not second homes owned by the wealthy for their recreational use) 11,177,000

Units vacant because they’re in the process of being rented or sold:

For rent 3,224,000

For sale only 757,000

Rented or Sold 783,000

Held off Market (occasional use, temporarily occupied, other) 6,414,000

Seasonal (i.e. second homes owned by the wealthy for their recreational use) 3,583,000

TOTAL Held off Market and Seasonal / Recreational: 9,997,000

In summary: there are 14.7 million vacant dwellings in the US, of which 10 million are not available for year-round rentals or sale. Those 10 million dwellings are comparable to the total number of dwellings in entire nations, for example, Australia (11 million housing units, population of 27 million).

There are many complexities not specified or included in these statistics. For example, vacant dwellings located in rural locales with few jobs might be empty because there is little demand due to a declining population. Other dwellings may no longer be habitable without renovation or repair.

On the other side of the equation, non-permitted dwellings (granny flats, etc.) may also be uncounted as those answering Census Bureau questionnaires might hesitate to report units added without official approval. This can include everything from RVs parked alongside homes to converted garages to living rooms partitioned off and rented out as quasi-bedrooms.

The vagarities of self-reported data are potentially major factors in counting short-term vacation rentals, a.k.a. AirBnB / VRBO-type rentals. Data remains sketchy on exactly how many housing units are being “held off the market” as short-term vacation rentals. As of 2023, there were 2,459,260 available vacation rental listings in the U.S., but this may not include informal rentals, rentals listed outside of the major platforms, etc.

The Census Bureau offers several estimates of seasonal units: 3.6 million in the above link, and 4.3 million vacant seasonal units in this post: See a Vacant Home? It May Not be For Sale or Rent. These are traditionally second or third homes of wealthy households. but many such properties are now being offered as short-term vacation rentals for periods when the owners aren’t using the property.

What these statistics don’t tell us is how many housing units have been snapped up by wealthy households as investments, nominally as “second homes” but solely as safe places to park excess capital / credit, not for recreational use. The wealthy may have joined the rush to cash in on the short-term vacation rentals boom, but they don’t need positive cash flow to afford the costs of ownership; the Airbnb rental income was mostly to defray the costs of ownership.

Too Many Rich People Bought Airbnbs. Now They’re Sitting Empty

In other words, one factor in the “housing shortage” is the pressure on the wealthiest households to find places to park their excess capital and exploit their low-cost lines of credit. This can be understood as a second-order effect of the Federal Reserve’s policy of inflating asset bubbles in which 90% of the gains flowed to the top 10% households. This new wealth could then be tapped to buy real estate, a long-favored asset class of the wealthy that has risen to new heights as the wealthy compete with other wealthy households to snap up housing.

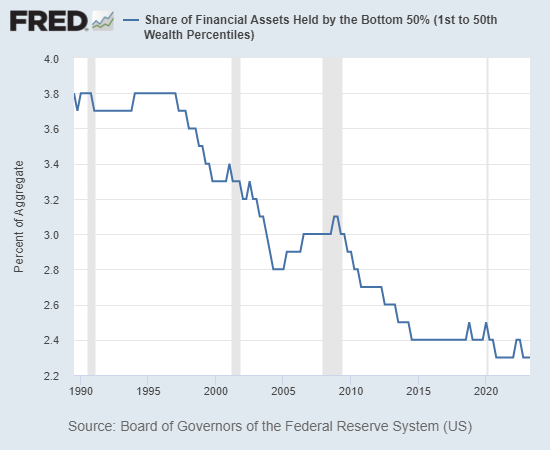

There’s not much in the pockets of the bottom 50% to compete with the top 5% for housing: we can expand this to say there isn’t enough in the pockets of the bottom 90% to compete with the top 10% who collected 90% of the gains of the Fed’s credit-asset bubbles:

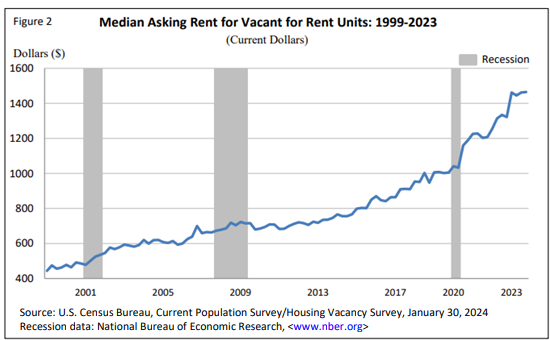

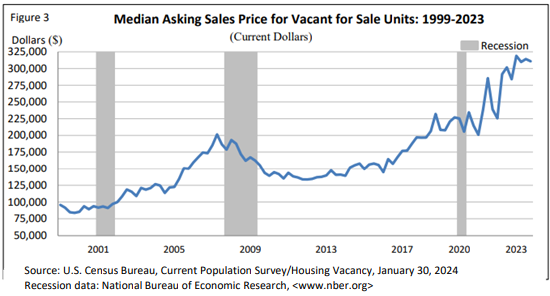

We can see how much rental and sales prices have risen in the past few years: charts are courtesy of the US Census Bureau.

Median asking rent for vacant rental units, nationally:

Median asking sales price for vacant for sale units, nationally:

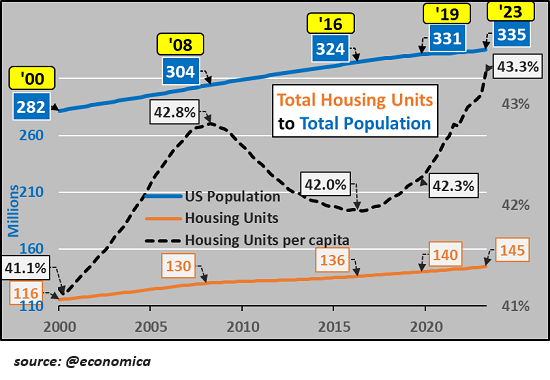

Meanwhile, housing units per capita is hitting record highs. This doesn’t support the claim that there aren’t enough housing units; it supports the idea that housing has been hoarded as an asset class, concentrated in the hands of those seeking vacation rental profits or appreciation on housing left purposefully vacant because renting it out is a hassle.

Would a couple million housing units entering the year-round rental market relieve some of the pressure pushing rents into orbit? Basic supply-and-demand suggests the answer is yes.

What happens when central bank manipulations of credit and interest rates reward the few with 90% of the gains generated by policies seeking to goose “the wealth effect”? The entire economy becomes distorted by the speculative frenzy to snap up assets that will appreciate as the Fed’s bubbles continue expanding.

Those seeking to buy a house as shelter for their household can’t compete with the wealthy seeking assets to snap up and hoard for appreciation. Those seeking to rent a dwelling are up against corporate hoarders of homes such as Blackrock, which owns 7% of all rentals in the US, and wealthy households pulling dwellings out of the year-round rental market to feast on the profits generated by revenge-spending vacationers.

Would a deep recession incentivize an increase in the number of occupants per dwelling and a corresponding decline in demand for rentals? Would a collapse of The Everything Bubble prompt some selling of hoarded housing? As painful as these might be, these dynamics would correct the destabilizing distortions wrought by the Fed’s easy-money bubble blowing and concentration of wealth in the hands of the few at the expense of the many.