Jay Leno once quipped about the Obama meal. “Order anything you want and hand the bill to the person standing behind you.” Biden, like his boss Obama, is praciticing a similar strategy. Spend like a drunken sailor and just keep borrowing until the whole thing breaks.

The barrage of fresh Treasury bills poised to hit the market over the next few months is merely a prelude of what’s yet to come: a wave of longer-term debt sales that’s seen driving bond yields even higher.

Sales of government notes and bonds are set to begin rising in August, with net new issuance estimated to top $1 trillion in 2023 and nearly double next year to fund a widening deficit. The Treasury is already in the middle of an estimated $1 trillion bump in bills as it seeks to replenish its cash coffers in the wake of the debt-limit deal.

It’s an explosive mix for borrowing costs as debt sales are swelling and the Federal Reserve continues to reduce its balance sheet at a time when traditional buyers of Treasuries overseas are discouraged by currency hedging costs.

“A worsening fiscal profile, amid fairly modest spending cuts, suggests that the upcoming supply deluge will not be limited to T-bills,” wrote Anshul Pradhan, head of US rates strategy at Barclays Plc. “The Treasury will soon need to increase auction sizes meaningfully across the curve. We believe the rates market is too complacent.”

Barclays strategists predict the net rise in coupon-bearing debt from August to year-end will be nearly $600 billion. And that would only ramp up in 2024, they say, with an annual figure of $1.7 trillion. That would be nearly double this year’s expected debt issuance.

Pradhan says he doesn’t think the market appreciates the increase in issuance that’s going to be needed due to wide budget deficits and the fact the Treasury won’t want bills to become a substantial share of the total debt.

Total net new bill sales are set to bring their share of US debt to about 20%, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co. The issuance would hit a threshold seen by the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee as the upper limit for the US to fund deficits at the least possible cost to taxpayers.

Bank of America Corp. says the supply deluge could result in a “demand vacuum” for longer maturity bonds that could push yields higher and tighten financial conditions.

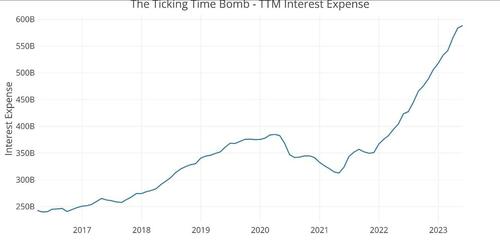

The problem isn’t purely a function of more debt. The bigger issue is that this new debt comes with a much steeper price tag. Interest on the national debt is rising at an alarming clip.

The trailing 12-month (TTM) interest on the debt clocked in at just under $600 billion in May. This was up from $350 billion at the start of 2022, less than 18 months ago. The government has added an extra $250 billion in expenses per year on just debt service.

This is just the beginning of an upward trend. Based on the current interest payments, the Treasury is paying less than 2% interest on the total debt. But a lot of the debt currently on the books was financed at very low rates before the Federal Reserve started its hiking cycle. Every month, some of that super-low-yielding paper matures and has to be replaced by bills, notes and bonds yielding much higher rates. That means interest payments will quickly climb much higher unless rates fall.

Looking at the Treasury sale on June 26 reveals the extent of the problem. The Treasury sold $162 billion in securities, with $120 billion in short-term Treasury bills with high yields.

- $58 billion in six-month bills at an investment yield of 5.45%

- $62 billion in three-month bills at an investment yield of 5.34%.

- $42 billion in two-year notes at a high yield of 4.67%, amid very strong demand. Longer-term yields are still far below short-term yields.

With this flood of Treasury bills, the share of short-term paper underpinning the debt is approaching 20%. That’s considered the upper limit, meaning the Treasury will soon have to turn to issuing longer-term notes and bonds. That means the Treasury will be locking in higher interest rates for the long term.

Tweedle dee and tweedle dum(ber).