The BRICS nations (originally Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) are meeting in Russia this week, and many alternative economics writers are making much of how these nations will be working hard to replace the dollar, but it is really nowhere near as simple as a united front to dethrone the dollar as the world reserve currency.

Now that 32 nations are meeting at the BRICS summit, talk of the dollar’s collapse to a new competitor has grown again as it did last year when BRICS met and did absolutely nothing in that direction. The growing number of nations willing to work in this economic bloc together is portrayed as a sign of growing and imminent threat against the dollar. The theory is that taking down the dollar as the global trade currency will crush the dollar and badly damage the US. Maybe it would—if they could do that—but that is very far away from what is happening. (On a long enough timeline, of course, anything is possible.)

Any attempt by the BRICS to collapse the dollar will face a mountain of troubles far greater than the dollar’s former feared serious replacement—the euro—or the solo ne’er-do-well attempt by the Chinese renminbi. Think, for example, of how the euro’s repeated weakness has been that various European national economies are so different in their needs that we find ourselves repeatedly talking about exits from the euro because one nation’s needed austerity is another nation’s death grip.

Well, the nations involved in BRICS are way more diverse than European nations, which, at least, share a common Western culture. Economically, they have even greater differences as well. So, you know the reality is that over time, they are going to be more fraught with conflict than the Eurozone has been. In fact, some of them are practically arch enemies.

Even getting a new currency started is highly problematic, much less the far more difficult job of building it up to where it can compete with the dollar. China and India exist on the fringes of war together all the time, conflicting over Himalayan regions. While Russia and China incline toward a currency based on the Chinese renminbi, India absolutely does not want anything that gives China more power in the bloc.

That sentiment is broader than just India. One economist from Hong Kong, which has its own strained relationship with its new mother country, China, says,

“The future of the grouping is uncertain, given its heavy economic dependence on China and the deteriorating sentiment toward China among its members.”

Also, while China and Russia are on the fringe of war directly with the US over Taiwan and Ukraine respectively, some of the other nations remain major trading partners with the US and don’t want to damage their relationship with the US or the rest of the West at all. Brazil and South Africa both agree with India’s stance against doing anything that would be seen as hurting the US.

Even as the grouping attracts growing interest as a political and economic counterweight to the West, tensions are simmering over its direction and influence. Members are split over efforts to reduce reliance on the dollar as a global reserve currency, and on the wisdom of continued expansion of the group.

In fact, with every expansion, the group becomes even less cohesive due to a greater number of competing interests. One new member that was admitted last year—Argentina—has already pulled out under its new president; and another—Saudi Arabia—has remained distant. So, there wasn’t as much kumbayah as originally feared (or wished for?) by the dollar doomers.

Not only is the growing group becoming as disparate as the United Nations, it is even taking on contours like the UN. India now favors two classes of nations, as we have in the UN with its security council that has special privileges and powers that the rest of the nations do not have. (Necessary to get those major players involved that evolved out of their status as victor nations in WW1.) India wants restricted entry of new nations and wants any new nations coming in to have restricted voting rights once they are in as a safeguard to how far things can go.

It wants to steer the group away from becoming an anti-US body dominated by China and Russia, Indian officials said on condition of anonymity.

Likewise …

Any bid to dilute South Africa’s influence by inviting Nigeria or Morocco into BRICS will be resisted, said the South African officials.

Even China currently regards a de-dollarized payment system, yearned for by Russia, as too ambitious. China’s economy is struggling badly, in part because of its zero-Covid policies that badly crippled its own economy and in part due to a massive trade war that began under Trump and has continued under Biden. Doing further damage to their own economy by destroying already badly dented trade relations does not appear to be something practical Chinese business leaders savor.

The United Arab Emirates, also happy to have healthy trade with many Western nations, including particularly good trade relations with the US, resists any efforts that would pit BRICS membership as opposition to the West. They have no desire to mess up a good thing.

I’ve held this view about BRICS from the beginning of conversations about how it will crush the dollar, and it has only grown more assured as time has gone on. That appears to also be the case with the guy who coined the term “BRICS”:

Jim O’Neill, the Goldman Sachs economist who first coined the BRIC acronym in 2001, said expansion had made the group “highly political.” He told a forum in London in November: “I am not sure what fruitful purpose it serves other than being a club that the US is not a part of.”

So, while the size of BRICS grows, its cohesion shrinks. The area that a new currency could hold sway over grows, but the likelihood of a new currency emerging becomes more problematic because of some pretty intense differences about whose currency should be the basis. In the end, they could resolve that by making no currency the basis and using gold, but that would not resolve their concerns about some nations having more power in the bloc than others—a status some expect to hold in legal writ for good.

Strong ties with the West by members inside of BRICS come with other problems as well:

Putin stayed away from last year’s BRICS summit after South Africa warned it would have to comply with an arrest warrant against him for alleged war crimes in Ukraine issued by the International Criminal Court in March last year.

Besides showcasing Russian strength, one big reason Russia is hosting the annual summit this year is likely that Putin would be at risk attending in some other nations and that those nations don’t want to defy the West by ignoring The Hague.

The current BRICS meetings remain more exploratory than anything in nature, so we’ll see how things evolve; but the idea of a strong currency seems highly problematic because of the deep political fractures throughout the group. We know the euro never came close to replacing the dollar (and maybe it never even wanted to), but this group raises the obstacles by an order of magnitude.

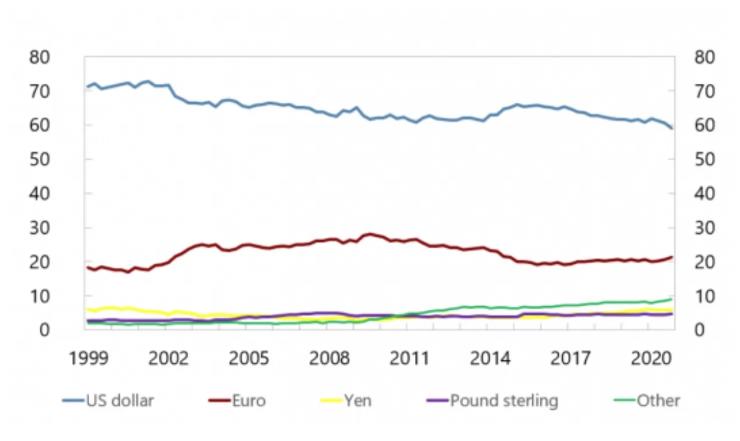

The dollar is more likely to continue slow decline through its own mismanagement as Republican and Democratic presidents alike have presided over enormous ballooning expansion of US debt, forcing a lot more dollars to find homes into global markets, and as the US seems intent upon using the dollar as a fairly ineffective club against nations that step out of line. As you can see below has been the case for decades, it won’t be so much a single currency rising to out-compete it, as it will be its own continued erosion, which looks like this (wherein the recently feared Chinese renminbi remains lumped in with all others in order to even put in a showing):

As Mark Twain once said, “Reports of my recent demise were greatly exaggerated.”