Authored by Charles Hugh-Smith via oftwominds,

The core skill going forward–frugality–is largely a forgotten skillset. Time to get busy while we still have time.

There are core systemic dynamics that are impervious to technological or financial gimmicks, and as they play out, a hard rain is going to fall:

1) The credit-business cycle. The credit-business cycle has been pushed forward for the past 15 years, and arguably for the past 24 years. The last “real recession”–the organic contraction of credit and risk-taking that drains the excesses from the economy and financial system over the course of several years–occurred 43 years ago in 1981-82.

The mechanism for pushing this essential cleansing is moral hazard, the disconnection of risk from consequence by unprecedented central bank monetary stimulus and central state fiscal stimulus. The net result of moral hazard is the excesses of risk and debt are rewarded and expand to even more precarious heights, ensuring the eventual downturn will be far more destructive than had the system been allowed to fully re-set in 2000-02 and again in 2008-09.

2) The reversal of financialization and the collapse of the Everything Bubble and the wealth effect. The commoditization of credit, leverage and speculation is a boon when first introduced to a credit-starved economy, but once the productive investments have been made, financialization continues expanding into extremes of debt, leverage and speculation.

Central banks have used one trick to keep the expansion going: they dropped interest rates to zero, enabling borrowers and speculators to borrow / leverage more with the same income. This expansion of credit boosted assets to extreme valuations as all this new “money” chased a limited quantity of assets. The credit-asset bubble increases the value of the collateral–the house, the stock portfolio, etc.–which then supports additional borrowing / leverage.

The payoff was not just putting off the credit cycle–the credit-asset bubble generated a massive wealth effect for those who owned the assets before the bubble multiplied their value. The top 10% who own 93% of all stocks have seen their net worth expand by tens of trillions of dollars, enabling their spending to account for roughly half of all consumption.

The resulting extreme of wealth-income inequality has social repercussions that are not yet fully realized, but the pressure on those left behind is mounting.

Interest rate cycles are multi-year affairs, generally running between 15 and 40 years. The current cycle–from 1981 to the present–is extremely long in tooth, reflecting the financial repression of interest rates over the past 15 years.

Nothing lasts forever, regardless of what policy is applied. Interest rates are rising and will continue to rise.

This means that central banks’ favorite trick to put off the credit cycle–lowering interest rates to zero–is slipping out of reach. This means that central banks will no longer be able to keep the credit-asset bubble inflated. It will deflate as interest rates rise, unpayable debt is defaulted and risk emerges in force.

Once the credit-asset bubble deflates, the wealth effect reverses, and consumption plummets as all those who rode the bubble higher are now poorer. The net result is the economy slides into recession.

Central states have piled up such a mountain of obligations and debt that their ability to stimulate the economy out of a much-needed cleansing of bad debt and speculative excess is limited.

So neither central banks and central states have the capacity to push the credit cycle forward any longer. The games have all been played and now the bill is due and payable.

3) The reversal of globalization. central banks were given the one-time luxury of lowering interest rates to zero by one dynamic: the emergence of China as the global exporter of deflation and a new “credit impulse.” As the developed economies shifted production to China, costs declined and profits soared, fueling the stock market bubble and offsetting the inflationary pressures generated by expanding credit and fiscal stimulus.

China has now matured to the point that it no longer exports either deflation or the credit impulse. Now the inflationary pressures of expanding credit and fiscal stimulus are not being offset, so they’re finally manifesting globally. There is no replacement of China’s one-time gift of deflation and credit expansion, and so inflation and interest rates will rise.

Throwing more money into the system will only accelerate inflation and interest rates. That game is over: checkmate.

4) The limits of scale. The latest technological advance on the lab bench rarely scales up: vaporizing plastic waste is nice, but the cost and inherent limitations of this “advance” mean it will remain a curiosity, not a global solution that magically eliminates the 400+ million tons of plastic waste that isn’t recycled, out of the 450 million tons of plastic produced annually.

Even when a new technology may make financial and practical sense, the time and money required to scale it up t useful levels are significant. Consider the “next big thing” in nuclear power, Small Modular Reactors. The first one is slated to come online in 2030, but such projects are typically plagued by cost and time over-runs in the early stages of development.

If the goal is to build 100 such reactors, how log will that take, and how much capital will it consume?

Will it take a decade? or two decades?

The point here is we’re entering a credit cycle recession with the infrastructure we have, and improvements will be incremental, time-consuming and expensive, draining capital from consumption, in effect deepening the recession. This is the dynamic I endeavor to illuminate in the 1970s, when vast sums of capital were invested in pollution mitigation and the upgrading of the nation’s industrial base, with only modest payback in the near-term. The real benefits only accrued decades later.

A similar upgrading of the nation’s industrial base is starting, but it will be a drain on consumption for decades to come.

5) The downsides of centralization. Optimizing profits has relentlessly driven centralization on every scale: a handful of corporations dominate every sector, and facilities–from slaughterhouses to chemical storage–are geographically centralized, inherently increasing the risk of “normal accidents” triggering catastrophic losses. This reality was explained by Charles Perrow in his book The Next Catastrophe: Reducing Our Vulnerabilities to Natural, Industrial, and Terrorist Disasters.

Decentralizing the economy increases costs, reducing profitability and pushing prices higher. This is the cost of resilience and redundancy. The cost of centralization is invisible until it’s too late.

6) Climate extremes. Setting aside the debate about causal factors, that extremes of weather are increasing in number and intensity globally is placing agriculture and infrastructure at greater risk of cascading, non-linear avalanches of consequences. Centralization adds to these risks.

Add all this up and we have a recipe for global recession in which inflation and interest rates rise, The Everything Bubble pops, possibly violently, the wealth effect vanishes into thin air, consumption plummets and job losses soar. Central banks and central states will not be able to push the credit cycle (i.e. recession) forward any longer, and if they try to do so, they will only make the decline more severe and painful.

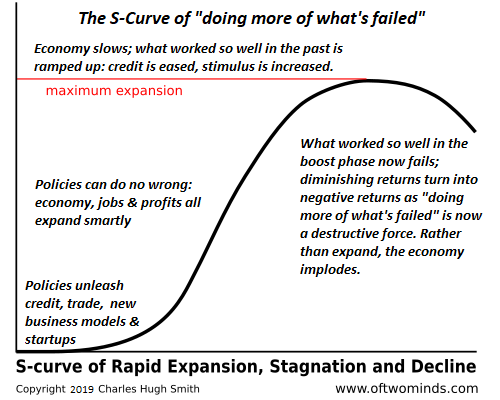

I often post this chart of the S-Curve to emphasize that cycles are organic and cannot be reversed or pushed forward forever. Pushing them forward has only increased the bill that must now be paid.

Our hubristic faith in the god-like powers of technology and central banks / states creates an illusion that the credit cycle turning is the result of a “policy error,” when in fact it’s just the way systems function. We’ve created extremely fragile, centralized systems optimized for profit, and operated on the false premise that all systems are infinitely controllable given the right technology or policy.

The result of our hubris is that the turning of systemic cycles will be more disruptive and painful than was necessary, as a direct result of our attempt to manipulate / rig the system to suit our expedient, short-term desires.

A hard rain is going to fall, and we serve our best interests by preparing for the coming storm.

The core skill going forward–frugality–is largely a forgotten skillset. Time to get busy while we still have time.

New podcast: How Asset Deflation Could Play Out (35:37 min)

Views: 849