Authored by Charles Hugh-Smith via oftwominds,

Fortunately, there’s an obvious answer staring us in the face: Tax the Casino.

There is a generational war underway in the U.S., and to date the young generations have lost and the senior generations have won. In numerous posts over the past 15 years, I have endeavored to compare apples-to-apples to show that the generations that came of age in the 1960s through the 1990s could afford to own a house and raise a family with moderate incomes. This is no longer the case.

Apologists for the status quo disagree, of course, but they are unable to contest an accurate apples-to-apples comparison of the purchasing power of an hour of labor then and now. We can say an hour of wages bought more goods and services then than it does today, or we can say “everything was cheaper then.” Regardless of the dynamics behind the devaluation of an hour’s labor and the stratospheric rise in the cost of healthcare, housing, childcare, college tuition, etc., the reality is well-illustrated by one example: a young couple who bought a modest house in 1996 in the East Bay of the pricey San Francisco Bay Area. (These are friends of mine, so this is a factual account, not a theoretical example.)

Each worked part-time for the city library, at rates of pay and with benefits that were sufficient to get by but were nowhere close to median full-time wages: remember, these are part-time workers working around 30 hours a week.

With a modest down payment and income they qualified to buy a small, old house (built in 1916) on a small lot in an East Bay suburb–the classic starter home–in 1996 for $135,000. (The lot is too small to allow a garage next to the house or a driveway to a rear garage. It’s small.)

Both were handy and slowly upgraded / remodeled the house with new heating, built new kitchen cabinetry, added insulation, new paint, updated bathroom, etc., over the course of a few years, at a cost in cash outlays of around $15,000, putting their total investment at $150,000, plus their labor of around $20,000. (Remember, these are 1997 dollars, so their $35,000 investment of materials and labor then would now cost $67,500 according to the BLS Inflation Calculator, which understates the soaring costs of building materials and labor.)

Note that they did not add a single square foot of additional space.

So let’s say their total investment was around $170,000. By the modest standards of housing appreciation in the 1990s, they would have been doing very well to sell the house for $200,000 a few years down the road.

But then Housing Bubble #1 inflated (thank you, FHA, corrupt rating agencies, loose-money Federal Reserve and asleep-at-the-wheel regulators), and so they sold the small house for $542,000 in 2004.

Needless to say, their hourly wage did not triple in those eight years, nor could they have scraped up the 20% down payment on a $542,000 house ($108,000) with their moderate incomes. What was within reach in 1996 was completely, totally out of reach a few years later.

Fast-forward 20 years and the house is valued at $1.3 million, down from $1.4 million (such a deal!). A 20% down payment is $260,000 and the buyer will need somewhere in the neighborhood of $250,000 to $300,000 annual income to qualify for the $1 million mortgage.

In other words, not two part-time librarians. This is the generational divide in a nutshell, and to complete the picture, add in the skyrocketing cost of healthcare, childcare, etc. in the 27 years since they bought the modest home for an affordable price.

Calculated in the number of hours of work needed to buy the house in 1996 and today, the difference says all we need to know about the generational divide: according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the median annual salary in the US is $56,420 and the average annual salary is $60,575. Let’s call it $30 per hour. Since California is a high-wage state, let’s call it $34 per hour. In California in 1996, the average annual pay was $31,773, or roughly $16 per hour.

In 1996, it took 8,437 hours (without deductions for simplicity’s sake) to buy a $135,000 house.

In 2023, it takes 38,235 hours to buy the same house for $1.3 million.

It takes 4.5 times more hours of labor to buy the same house today. Fellow citizens, I could go through the same apples-to-apples comparison of the hours of labor required to pay for healthcare insurance, 24 hours in a hospital, a month of childcare or state university tuition, and the results would be equally crushing.

For example:

University of California at Davis:

2004 in-state tuition $5,684

2018 in-state tuition $14,463

The apologists always have quibbles. But the quality of the goods and services we have now are so much better. Not just wrong–totally wrong: The “Crapification” of the U.S. Economy Is Now Complete (February 9, 2022)

Stainless Steal (February 26, 2023)

But California is an extreme; the median home price in the U.S. is only $400,000. In 1996, the median home price in the U.S. was $140,000. Average annual earnings in 1996: $29,000. Average annual earnings in 2023: $60,000.

So it took 4.8 years of work to buy a house in 1996 and it now takes 6.7 years. That’s 40% more hours of work to buy a house. Never mind prices or inflation, both of which can be distorted and misleading: how many hours of labor does it take to buy a median-price house? Do the same calculation for childcare, healthcare and college tuition, and you get the same results:

What was within reach of the majority of average two-income households is no longer within reach. All of the quibbles in the universe don’t change the fact that the older generations that bought assets at prevailing prices 25 or more years ago have banked enormous gains in their personal wealth, not through any particular genius or special effort but solely as the result of their entry into the economy pre-bubble.

These enormous gains in personal wealth have helped older generations offset the recent ravages of much higher costs of living (i.e. inflation). Many other benefits have accrued to those who bought assets pre-bubble, for example, in states with limits on property tax increases, the low initial purchase price of their home has locked in property taxes that are a fraction of the property taxes paid by recent buyers.

All of which leads me to this: isn’t it time that we have Social Security for families with children, just as we do for seniors? Okay, now that the screaming and weeping and gnashing of teeth have subsided, I hear a plaintive cry: how are we going to pay for such a costly program?

Fortunately, there’s an obvious answer staring us in the face: Tax the Casino, by which I mean institute a transaction tax on every transaction of buying, selling or transferring by any means any asset or financial instrument of any nature.

Okay, so the screaming and weeping and gnashing of teeth is even louder now, but after the rational mind once again becomes available for dialog, we can note that a 2% transaction fee on a $1,000 stock purchase is $20. Those who were trading stocks in the 1980s recall that buying $1,000 of stock in a brokerage account cost $54 or more in commission and fees. So the claim that a 2% transaction tax would cripple the nation is not based in historical fact.

In the booming 1980s, commissions on stocks and options were as high as 5%, and that didn’t cripple the economy. Transaction fees at 5% suppress daytrading and high-frequency trading (HFT), i.e. totally unproductive skimming of wealth by financial trickery, but they don’t impair long-term investing in productive assets.

In summary: a 2% transaction tax would have zero impact on legitimate investing and offer a useful suppression of unproductive skimming operations. Maybe capital would be incentivized to seek real-world long-term investments instead of financier/rentier skims and scams. As for real estate, many locales already have real estate transaction fees, and that fee is simply added to all the other commissions and fees. If the buyer can’t afford their share of a 2% transaction tax, they have no business buying the property in the first place.

A modest 2% transaction tax on every asset-financial transaction in the U.S.–every stock, option, futures contract, derivative, cryptocurrency, ETF, mutual fund, rental property, commercial building, corporate merger, issuance of stock options, the sale of fine art and collectible autos–everything–would raise a rather large sum.

I’ll discuss this further in a follow-up post, but let’s be honest: such a transaction tax would go a long way to raising enough money to provide some cash payments to help non-wealthy families with children.

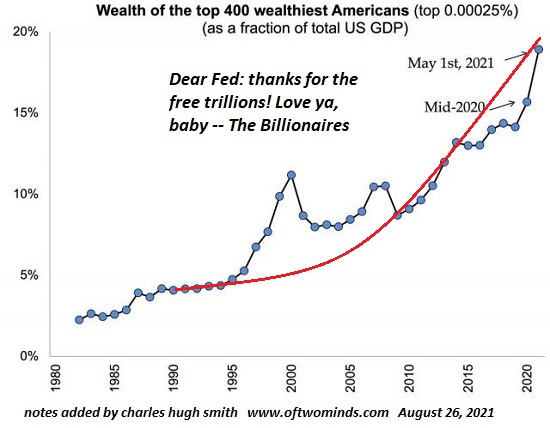

Those profiteering from the Casino will scream and weep, but the United States does not exist to enrich the few at the expense of the many or the common good. I know this is a shocking revelation, as it now seems that the nation does exist to enable the few to profit at the expense of the many, and it may be time to reclaim the interests of the nation and its citizenry and put them ahead of the private interests of bankers, Corporate insiders, financiers, rapacious cartels and monopolistic billionaires.

Yes, the devil is in the details, but let’s stick with the overall context: there’s $156 trillion in U.S. assets (plus foreign capital buying U.S. assets) sloshing around the U.S. economy, assets that are constantly being bought and sold, and 2% of all transactions would go a long way to supporting the families with children who aren’t wealthy.

Or we accept a needless, divisive, incredibly destructive generational war to protect the infinite greed of those skimming wealth in the Casino. It’s our choice, but it doesn’t strike me as much of a choice.

More Than Half of US Wealth Belongs to Baby Boomers:

Baby boomers: $78.1 trillion (50%)

Generation X: $46 trillion (29.5%)

Silent Generation: $18.6 trillion (11.9%)

Millennials: $13.3 trillion (8.5%)

Generation Z: Insufficient data

Visualizing $156 Trillion in U.S. Assets, by Generation

The gig economy sucked in millennials like me. Will we ever get out?

New podcast: Self Reliance (45 min).