via moneymetals:

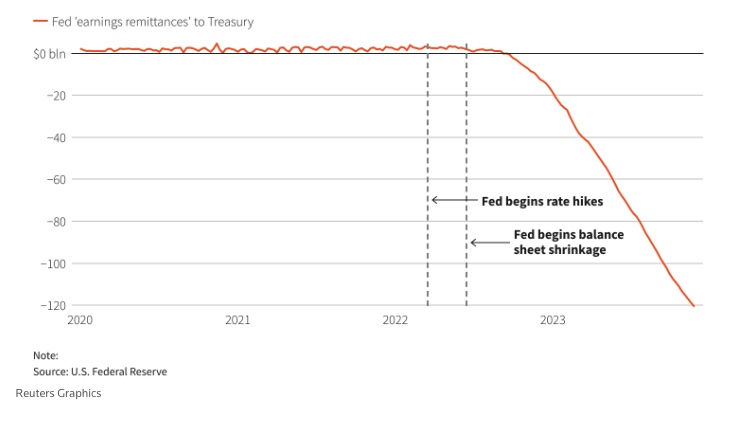

The Federal Reserve recorded a record loss of $114.3 billion in 2023, and you (the American taxpayer) are on the hook.

The last time the Fed ran a net operating loss was 1915.

The loss was a direct result of the Fed’s interest rate hikes to fight price inflation.

Rising interest rates create big problems for the Fed. It earns interest income on the bonds it holds on its balance sheet. But the central bank also pays interest to banks and financial institutions that park money there.

The problem is the bonds the Fed purchased during multiple rounds of quantitative easing (QE) were relatively low-yielding. But having pushed interest rates much higher, it is paying interest at a much higher rate.

The St. Louis Fed explained it this way.

Tightening causes the net interest rate spread to fall; that is, it causes net income to fall for a constant size of the Fed’s balance sheet. This occurs because the Fed runs a maturity mismatch: It owns long-term securities and owes short-term liabilities.

Specifically, when the Fed raises the policy rate, it is immediately paying more interest on bank reserves and reverse repos—a large portion of the Fed’s liabilities: 42.5 percent and 17.0 percent, respectively, as of Nov. 8, 2023. However, the Fed’s assets are longer-term and often pay a fixed interest rate. Therefore, when the Fed raises the policy rate, its net interest rate spread falls.

According to the Fed’s income statement, it paid out $281.1 billion in interest during 2023. That compares with $102.4 billion in 2022. Meanwhile, it earned interest from its bond portfolio totaling $163.8 billion last year. That was a slight decline from $170 billion in 2022.

The drop in interest income stems from a modest reduction in the Fed’s balance sheet as part of its inflation fight. According to the St. Louis Fed, “Tighter monetary policy also tends to be associated with a reduction in the size of the Fed’s balance sheet. For a given (positive) net interest rate spread, this reduces the absolute value of net income.”

The Fed Is Losing Billions! So What?

Generally, businesses experience pain when they lose money. But when the Federal Reserve loses money, the U.S. government feels the pain.

And that means you feel the pain. Because you (the taxpayer) will ultimately foot the bill.

Under the Federal Reserve charter, the central bank remits net operating profits to the U.S. Treasury. This serves as an income source for the federal government and lowers the budget deficit. But when the Fed loses money, the Treasury loses its payday. That results in even bigger budget deficits.

And who pays for those deficits?

You do.

Bigger deficits mean Congress either has to raise taxes, or the Treasury must borrow even more money. Either way, taxpayers pay. They either get a bigger tax bill, or they pay for the borrowing via the inflation tax when the Fed prints money to monetize the debt.

Meanwhile, it’s business as usual over at the Eccles Building.

Typically, managers must take drastic measures when their companies suffer big losses. They generally try to slash costs. Sometimes they lay off employees.

If losses mount high enough, they might have to borrow money or sell assets. If they can’t stop the business from bleeding red ink, the company will ultimately face bankruptcy.

When the Fed loses money, the central bankers don’t have to do anything other than some creative accounting.

We live in a universe where the Fed makes its own special accounting rules, and according to its own special accounting rules, a net loss magically transforms into a “deferred asset.”

You read that right. Losses become an “asset” on the Fed’s balance sheet.

The Fed explained the “deferred asset” like this.

[I]n the unlikely scenario in which realized losses were sufficiently large enough to result in an overall net income loss for the Reserve Banks, the Federal Reserve would still meet its financial obligations to cover operating expenses. In that case, remittances to the Treasury would be suspended and a deferred asset would be recorded on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet.

Under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, operating losses reduce a business’s reported capital or surplus.

But in Fed accounting, the central bank simply creates an “asset” on its balance sheet out of thin air equal to the loss. Business goes on as usual. If losses mount, the size of this “asset” grows.

In an article published by the Mises Wire last summer, Alex Pollock noted that without this accounting trick, the Fed would have negative capital.

Here are the combined Fed’s correct capital accounts as of June 30, based on Generally Accepted Accounting Principles. They result in a capital of negative $32 billion:

-

Paid-in capital $36 billion

-

Retained earnings ($68 billion)

-

Total capital ($32 billion)

As The Hill reported, “Among other things, this accounting ‘innovation’ ensures that the Fed can keep paying dividends on its stock.”

Don’t you wish the IRS would let you use “innovative” accounting on your tax returns?

It’s important to note that there is no limit to the size of a “deferred asset,” and it could theoretically exist forever.

According to Fed data, reported by Reuters, the deferred asset stood at $133 billion at the end of 2023. As of Jan. 10, it had increased to $136.9 billion.

Once the Fed starts making money again, it will reduce the amount of this imaginary asset. That means the U.S. Treasury won’t see another dime from the Fed until this “asset” is zeroed out.

According to an analysis by the St. Louis Fed, this won’t likely occur until 2027. An independent analyst told Reuters the life of this mythical “deferred asset” could extend into 2028.

This means as long as the Fed continues to lose money and during the time it pays down its “deferred asset,” the federal government will experience a reduction in revenue resulting in budget deficits higher than they otherwise would have been.

A revenue cut is less than ideal when Uncle Sam is already buried in debt and running massive budget deficits every single month. It means the U.S. government will have to borrow even more money that the Fed will ultimately have to monetize.

And it’s less than ideal for the U.S. taxpayer who will ultimately foot the bill for higher interest expense and the price inflation created as the Fed ultimately monetizes the debt.