by Chris Black

The Treasury’s new buyback program will have a humble beginning, but tremendous potential to become an essential tool with far reaching impact.

Treasury first hinted at a buyback program (https://fedguy.com/the-marginal-buyer/) last August amidst concerns over poor Treasury market liquidity and finally decided to launch it next year.

The most recent details (https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/221/TreasurySupplementalQRQ32023.pdf) indicate modest buyback amounts to both improve Treasury market liquidity and help the U.S. better manage its cash holdings.

The Treasury has explicitly dismissed any intention to use the program to alter it’s debt maturity profile (https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/221/TreasurySupplementalQRQ22023.pdf), so the program should not have asset price implications.

However, the infrastructure being set up could evolve to allow Treasury a greater role in monetary policy.

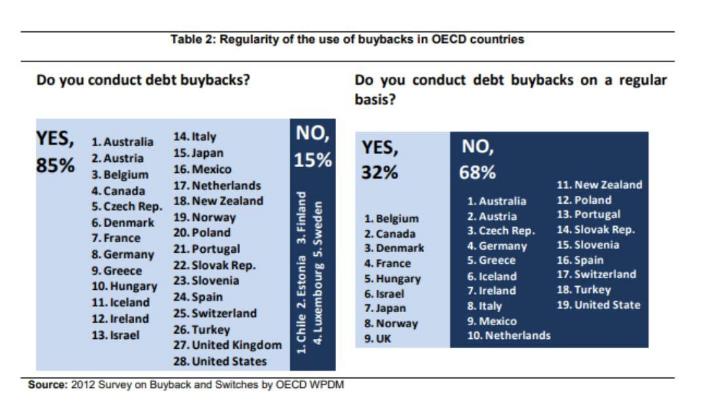

Buyback programs are simply the purchase of previously issued debt and are not uncommon among sovereigns. A number of OECD countries have active buyback programs for the same purposes as those stated by the Treasury.

In fact, the Treasury engaged in buybacks in 2000 (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1022669) when it used fiscal surpluses to retire higher yielding debt and save the taxpayer some interest expense.

The innovation today is the establishment of a standing buyback program that would be actively used throughout the year.

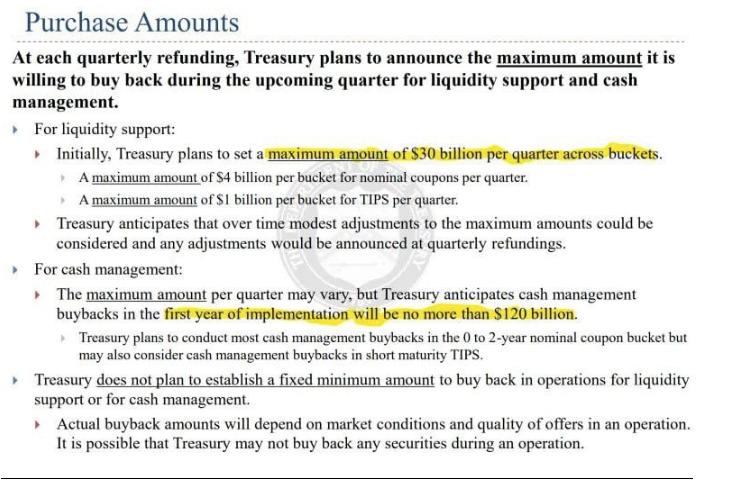

Although some aspects are not yet fully determined, the Treasury has shared its conceptual view of how the program would be implemented.

Treasury plans to issue a bit more debt at each auction with the understanding a portion of the proceeds would be used to purchase old debt.

In effect, the composition of Treasuries outstanding would be tilted towards the more liquid new issues.

Treasury anticipates that it will announce expected buyback amounts in advance each quarter when it is also announcing new issue sizes.

Although not explicit, Treasury appears to anticipate implementing buybacks through reverse auctions similar to how QE was conducted. In that case, primary dealers would put in an offer to sell a security and Treasury would decide whether or not to accept the offer based on certain metrics.

Treasury noted that it is still in the process of developing the specific metrics.

The buyback program is aimed to both improve liquidity in the Treasury market and to help the Treasury more effectively manage its cash balance.

Treasury’s cash balance can fluctuate due to unanticipated expenditures or seasonal tax flows.

For example, Treasury’s cash balance swelled in 2022 as the tremendous bull market in 2021 led to a surge in capital gains tax receipts.

The Treasury had more cash than it needed and could only get rid of it by passively paying down Treasury bills over the coming months.

A buyback program would have allowed Treasury to instead actively deploy that cash and buyback existing debt and save on interest expense sooner. Treasury anticipates that cash management buybacks would mostly be deployed around quarterly tax payment dates.

The more important use case for buybacks is to improve Treasury market liquidity. While Treasury securities are overall very liquid, each specific Treasury security becomes much less liquid over time.

The chart depicted illustrates this by showing that the bulk of trading volume is concentrated in recently issued Treasuries (“On the Runs”), while prior issues of Treasures (“Off the Runs”) have very limited trading. Investors have more trouble selling off the runs, which can even become illiquid at times of market stress (https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2022/07/the-global-dash-for-cash-in-march-2020/).

Treasury market liquidity as measured by bid-ask spread, market depth, and deviations from spline remains notably poorer than pre-2020 (https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/221/TBACCharge1Q32023.pdf).

A buyback program would improve it by “cleaning up” illiquid off the runs and replacing them with much more liquid on the runs.

The buyback program appears modest, but meaningfully expands the Treasury’s toolkit by allowing it to both add and remove duration into the market.

Previously, only the Fed took duration out of the market via QE and only the Treasury added duration through its choice of debt issuance.

While Treasury has stated that it would not modify the maturity profile of its debt with buybacks, the program gives it the capability to do so.

The buyback program will start its first year with only a maximum of $120b in liquidity buybacks and a maximum of $120b in cash management buybacks. It is hard to see $120b in annual purchases having a meaningful impact on Treasury market liquidity, which averages around $600b a day (https://www.finra.org/finra-data/browse-catalog/about-treasury/daily-data).

However, this is very likely just the beginning.

The Fed’s RRP Facility began with counterparty limits of $0.5b (https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/overnight-reverse-repurchase-operations-and-uncertainty-in-the-repo-market-20171019.html) that over time expanded to $160b per counterparty (https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/rrp_faq) as market needs evolved and comfort with the facility grew.

In the future the buyback program will almost certainly become much larger. Treasury market dislocations like those seen in March 2020 could potentially be solved by Treasury instead of the Fed.

And maybe the program could one day be deployed to influence monetary conditions. For example, Treasury could effectively ease financial conditions by issuing short dated debt to purchase longer dated debt. There is no indication of this today, but treasuries and the central banks do not always have the same goal and conflicts between the two are common in history (https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/treasury-fed-accord).

The fusion between Treasury and Fed policy, which took off to the races in 2020 (https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/files/monetary20200323b1.pdf), is ready to make its next historical leap into a deeper and immutable link. Remember, the New York Fed is a private entity of multinational member banks

(https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/files/newyorkfinstmt2022.pdf).

See BlackRock’s August 2019 white paper Going Direct (https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/whitepaper/bii-macro-perspectives-august-2019.pdf) for the outline.