Last week, gold set another all-time high price record. Today we discuss the forces driving gold’s price, specifically central banks and commodities contracts, and what to expect…

From Peter Reagan at Birch Gold Group

This week, Your News to Know rounds up the latest top stories involving gold and the overall economy. Stories include: Gold hits new all-time high of $2,460 in a highly volatile week, and the Bank of Japan pretends it can restore the yen.

Gold breaks $2,460 on expectations of a September rate cut

Gold has had one of the most volatile weeks in recent memory as it moved in a range of as much as $100. The main story in this volatility, of course, has been the hitting of another all-time high, this time $2,460.

The pullback was strong, as of latest leaving it around the $2,400 level and leaving many investors wondering what’s next. Do we entertain the bearish headlines? Well, the first thing to remember is that the bearish headlines have already been proven wrong. You only need a couple of seconds of looking to find headlines outright stating that gold won’t hit another all-time high in the near-term and that down is the only way to go.

Before moving on to some noted predictions, it’s worth mentioning that the driver for this latest swing up is being listed as a 100% expectation of a September rate cut. This might be one of the few, if not the only, instance this year where we agree with the mainstream on what’s pushing gold up.

A 100% expectation of a rate cut in two months means that the investors have priced it in in the most literal sense. It tells us what we can expect when the rate cuts do happen. There is a body of opinion that states nothing will happen immediately, precisely because the cut has already been priced in. Historical precedent on this varies: it might be true, it might not.

But we now know that market participants view any kind of dovish shift in sentiment as extremely bullish for gold. And how can they not? We’ve already mentioned analysts’ views that as many as two rate cuts have been priced in. It’s no surprise: the Federal Reserve needs to cut, and it needs to cut a lot. Who’s to tell where gold might end up when that particular cycle ends, along with the U.S. dollar? We have little doubt that this is a primary ingredient in all the $3,000-4,000 forecasts.

In the shorter-term, we have the likes of Morgan Stanley forecasting $2,600 by the end of the year. No small thing, especially given the growing view that 2025 will be the year for gold. And wouldn’t that be something, considering the almost unbelievable price action posted since the start of the year, one that has seen the supposedly non-yield-generating asset gain over $400.

But a somewhat buried and equally important story is that we’re seeing hedge funds make bullish bets on gold at record levels – along with an influx of buying.

Both trends are interesting for their own reasons.

In general, funds can be seen as the permabears of the gold market. They never seem to follow any kind of bullish sentiment, even when it’s financially responsible to do so. Any kind of elevated fund interest must be translated to something brewing in the gold market. And this makes that pretty clear:

Hedge funds and other large speculators boosted their net-long position in gold, often used as a hedge against rising political and economic uncertainty, to the highest in more than four years as of July 16, weekly U.S. government data published Friday showed. [emphasis added]

Since the start of the year, the lack of “open interest” in gold despite the intense price surge has been a major talking point for any careful observer. Here’s what open interest means:

Open interest is the total number of outstanding derivative contracts for an asset – such as options or futures – that have not been settled. Open interest keeps track of every open position in a particular contract rather than tracking the total volume traded…

Growing open interest represents new money coming into the gold market, while shrinking open interest tells us the opposite.

So what’s going on? How can today’s gold price be so high without significant open interest?

Here’s the thing: Open interest measures derivatives contracts, not demand for physical gold itself. Derivatives contracts are simply bets on the direction of gold’s price. That’s all. Options and futures contracts for virtually every financial asset exist and are actively traded – and the vast majority (98%) are settled in cash.

So the mystery of the lack of open interest for gold contracts is easily solved. Demand for physical gold is defining gold’s price today. When central banks buy gold, they purchase gold bullion bars and have trucks deliver them directly to their vaults. Clearly, measures of open interest simply don’t capture actual demand for physical gold.

Don’t confuse open interest in commodities contracts with actual demand for physical precious metals. Maybe this seems obvious to you but it’s the sort of nuance that trips up even veteran analysts sometimes. So much of the global financial system is illusory, just screens and spreadsheets talking to one another, that sometimes the players forget there are actual assets involved.

Fortunately, that’s not a concern Birch Gold Group customers have to worry about.

The Bank of Japan learns that destroying a currency is easy, but saving it is hard

By this point, you might almost not believe that the Bank of Japan is trying to restore the yen if we didn’t have a source to back up the claim. That skepticism is well-founded.

In only a few short years, the yen went from a safe haven on par with the Swiss franc to oscillating like a South American currency.

As we point out time and again, the path of every unbacked currency is down. This isn’t something only experienced analysts or economists know. It’s part of the premise! When the Federal Reserve adopted a “long-term average of 2%” as their inflation target, that means destroying 2% of the dollar’s purchasing power every year. Deliberately, on purpose, as part of their economic stabilization strategy.

That’s why every currency’s purchasing power declines. This is most visible when you look at gold price in the relevant currency, with records going back however many decades we’d like. This is a major reason gold’s price goes up.

So, after destroying a currency’s purchasing power, what if central banks want to rebuild it? Well, there’s not a lot they can do. Remember, central banks, along with Paul Krugman and other Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) adherents, are terrified of deflation. Even though increasing purchasing power would logically be helpful in any real attempt to restore a currency, you’re unlikely to see any public official or establishment economist say it.

Instead, they pretend that inflation is good and somehow necessary.

Destroying purchasing power is easy. Revitalizing a currency, giving it back purchasing power, is very difficult. So what do central banks do?

They bluff.

They hold press conferences. They write papers and op-eds and tell the whole world just how serious they are about restoring currency. They hope people will believe them – and will act as though it’s all true. And hope that’s enough!

Think about it: What is the current tightening cycle of the Federal Reserve, if not one big bluff? Here’s why:

- Higher interest rates lead to unsustainable federal government debt service payments ($1 trillion a year and rising)

- Higher interest rates blew up a handful of banks (so far) – survivors are still dealing with over half a trillion dollars of unrealized losses

- More expensive credit squeezes “pre-profit” start-ups and heavily indebted companies

- Mortgage rates have risen, along with home prices, to the point that the average family can no longer afford the average home

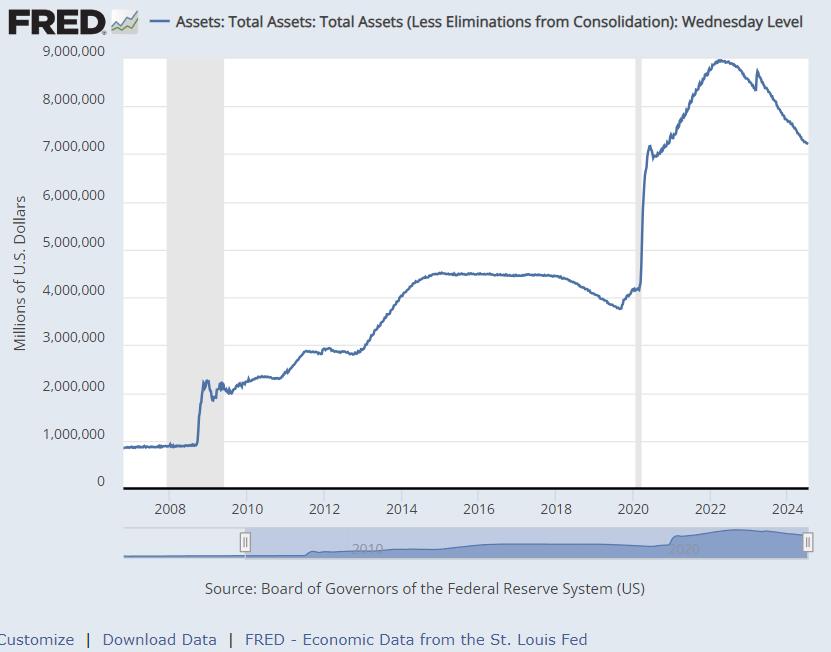

There’s more, of course, but it isn’t relevant. Take a look at the Fed’s balance sheet – note how much faster the line goes UP (money-printing) than DOWN (quantitative tightening):

To the credit of author Konstantin Oldenburger, he does explore the idea that a rising yen could benefit gold prices as hedge funds become even more averse to the Japanese currency. It would be yet another instance of a supposed overt headwind boosting gold, and we have seen no shortage of those recently.

But the analysis somewhat misses the point, and that is that whatever faith the Japanese yen might have enjoyed has been destroyed. Short of a gold tether, there is no restoring it. From a basic economics stance, it’s not really clear why the yen had any faith to begin with. On a good day, it had a more than 100-to-1 yen-to-dollar ratio. So why did everyone pretend for so long that it’s comparable to, say, the euro or the pound sterling?

So far, there are only rumors that the Bank of Japan and the Ministry of Finance intervened to facilitate positive yen action. But even if we get confirmation, we don’t see how it will matter. The yen is no greenback: hawkish rhetoric and policy changes won’t cut it when it comes to restoring global clout.

That’s not to say things are great for the greenback, either, as Sprott’s Kam Hesari warns us that U.S. debt is reaching a tipping point. While we’re not about to dismiss the notion, we have to wonder what that tipping point is. In the 2015-2016 run, Presidential candidate Donald Trump called a debt pile of $24 trillion a “point of no return,” somewhat reluctantly quoting economists in doing so.

Eight years later, that pile is right at $35 trillion. It seems logical that the debt tipping point is behind us. Everything else is pretense. Indeed, if we could somehow return to a debt pile of merely $24 trillion, it’d likely be called the greatest economic restoration in history. Undoing just the last eight years of damage looks impossible.

Now, it’s worth noting that the yen and the U.S. dollar aren’t exactly in the same spot when it comes to what’s been driving erosion. The yen’s woes come from the kind of loose monetary policy that makes the Fed seem like it’s stuck on a permanent Volcker script. But because of its global reserve status, the U.S. dollar’s debt pile and the crossing of whatever tipping point is trendy threatens to pull the entire global market into a crisis for the history books. One from which, we would imagine, gold will be the only way out.

Views: 411