Authored by Charles Hugh-Smith via oftwominds,

The key takeaway here is: don’t count on a simplistic ideology or reform or a “supreme leader” to save the status quo from internal failure.

Humans prefer simplicity to complexity. This is why mythologies still resonate with us, despite our hubristic claims to rationality and “following the science.” What we actually crave isn’t the challenge of teasing apart highly complex systems of interconnected dynamics in which each subsystem influences every other subsystem.

What we crave is a simplistic explanation / answer and a leader who we can follow because they keep repeating the simplistic answer. So we boil complicated systems such as societies and economies down to “capitalism” or ‘socialism,” and cling to simplistic versions of these ideas as the explanation of human nature and the answer to all our problems.

When these simple ideas fail to map reality, we’re forced to say things such as “ah, capitalism / socialism works wonderfully and perfectly, but we don’t have true capitalism / socialism,” with the unstated cause of this troublesome imperfection being, well, the pesky humans in the otherwise perfect system.

Which leads us to the present. A great many people cling to a simple reform which they believe will either solve all our problems at the root, or at least go a long way to setting the course that will solve all our problems. These reforms include: hard money / return to the gold standard; adopting bitcoin as the universal currency; seeking “market-driven solutions” to every problem, more regulatory oversight to make sure bad things stop happening, and so on.

If simple reforms / “getting back to basics” actually worked, history would be composed of well-run, boring utopias interrupted every so often by spots of bother that were quickly vanquished by one of the tried-and-true simple reforms. But this doesn’t map the historical record, which tends to exhibit long periods of stability characterized by complex city-states / empires establishing a system of governance and economic organization that is productive and adaptive to the predominate conditions of the era.

These stable system are eventually fatally disrupted by one or both of these forces:

1. The predominate conditions change dramatically, demanding adaptations that are beyond the capacity of the system that had worked so well for hundreds of years. These externalities include epidemics, long-term droughts, depletion of vital resources and invasion.

In some cases, these external forces overlap, generating a Polycrisis in whih each external challenge reinforces the others or depletes the system’s reserves to the point there is nothing left to deal with the last set of crises.

(To borrow a phrase from correspondent T.D., we can say that these crises got inside their OODA Loop–observe, orient, decide, act–leading to a fatal inability to react fast enough and decisively enough to meet the challenges successfully.)

2. The system’s internal limitations–invisible to the participants–fatally restrict the flexibility and adaptability needed to recognize and respond to gradually-developing weaknesses generated by the internal limitations. The weaknesses are papered over by underlings fearful of reporting the troubling truth–“everything’s perfectly all right now. We’re fine. We’re all fine here now, thank you”–or narrative control–the empire is forever, no worries–or the system responds by doing more of what’s failed spectacularly: the gods are angrier than we thought, sacrifice ten times more captives next time, that should do the trick.

Here is how Ray Huang, author of 1587, A Year of No Significance: The Ming Dynasty in Decline summarized the internal limits of the Ming Dynasty’s system 57 years before its final collapse in 1644:

“The year 1587 may seem to be insignificant; nevertheless, it is evident by that time the limit for the Ming dynasty had already been reached. It no longer mattered whether the ruler was conscientious or irresponsible, whether his chief counselor was enterprising or conformist, whether the generals were resourceful or incompetent, whether the civil officials were honest or corrupt, or whether the leading thinkers were radicals or conservatives–in the end they all failed to reach fulfillment.”

The status quo has already reached its limits and reform on any scale beyond the usual incremental “policy tweaks” is impossible, and it no longer matters who’s nominally in charge, if rulers are competent, officials are honest or corrupt, or thinkers are radicals or conservatives–the system is beset by forces it fostered but no longer controls, and indeed is incapable of controlling due to the intrinsic limits of the system’s core structures, limits which were invisible during the Boost Phase of rapid expansion.

The Ming Dynasty’s highly centralized system of governance was unified and guided by a Confucianist moral code rather than a highly developed system of laws and regulations. The current global status quo is unified and guided by a code based on a specific definition of Progress: the eternal growth of production and consumption of goods and services, and the eternal growth of the credit needed to fuel this growth in a permanent economic expansion in which whatever is labeled “innovative” is reckoned better than whatever it replaced. Any evidence to the contrary is dismissed as “negativity,” “Luddite,” and other derogatory labels: new is by definition the epitome of Progress.

It is now clear that “Progress” defined as whatever is “new” and “innovative” is in many cases the opposite of actual Progress–what I term anti-Progress–and so this simplistic ideological underpinning of the status quo is crumbling.

The “innovation” may well be highly profitable–financialization, globalization, social media, etc.–but its impact may be disruptive to the point that the system is internally incapable of responding fast enough and decisively enough to correct the resulting run to failure.

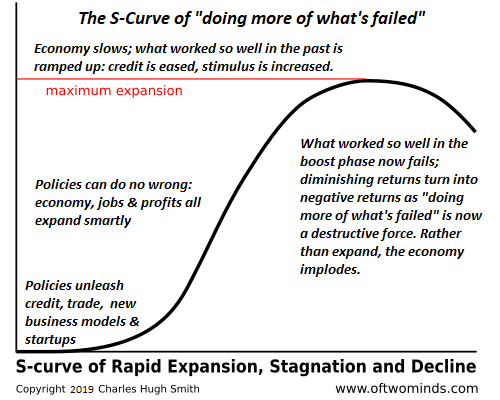

We can visualize the system reaching internal limits and the resulting decay of adaptability / run to failure as an S-curve:

Given the internal, structural limits, the entire system has only one pathway: decline to the point that a seemingly modest crisis disrupts the last shreds of coherence in an increasingly nonlinear system and the resulting asymmetric effect collapses the system.

The Ming Dynasty took 57 years to decay and collapse from 1587. Given the nonlinear dynamics and the inherent fragility of the status quo’s many dependency chains, this timeline could be reduced by an order of magnitude to 5.7 years. We won’t know until a crisis that would have been controllable in decades past generates asymmetric effects the system can no longer control.

The key takeaway here is: don’t count on a simplistic ideology or reform or a “supreme leader” to save the status quo from internal failure: we’re on our own, and it’s far better to face this daunting reality now rather than place our faith–and our passive inaction–on the altar of false gods.

Views: 160